Editor’s Note: From 1987 through 1994, diehard Steely Dan fans turned to a small fanzine called Metal Leg for information about Donald Fagen and Walter Becker. Published first by England’s Brian Sweet (who went on to write the unofficial band biography Steely Dan: Reelin’ In The Years) and later by New Yorkers Pete Fogel and Bill Pascador, Metal Leg set high standards by providing solid information without resorting to paparazzi-style tactics.

Articles

“Gaucho”-era interview with the Dan

Editor’s Note

Hi. Well, this is our fourth issue completed in the USA, and might I add, a bumper issue. And as long as Donald and Walter continue to leave their homes and work again, Metal Leg will get bigger and better!

For many of you, this is your last issue on your year’s subscription. If your time is up, you will find a subscription form enclosed so you can continue to receive another year of Metal Leg. Now that Donald’s new record is finally in sight, there will be a lot to read about.

I want to cut my editor’s note short because we need the room for more important matters. Lastly, I would like to dedicate this issue to Larry Carlton, whose playing has inspired me so much that I am now on my 47th copy of The Royal Scam.

–Pete Fogel

I Got The News

The Beacon Show

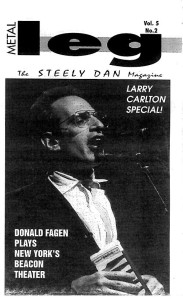

Once a year is better than nothing at all. That’s what was heard from the fans who attended the second annual New York Rock & Soul Revue at the Beacon Theater in New York City on March 1st and 2nd. Both sold-out nights attracted rock and soul fans from across the world to see the all-star lineup of Phoebe Snow, Michael McDonald, Boz Scaggs, Charles Brown and last, but not least, Donald Fagen.

The Metal Leg staff geared up for the event by obtaining 50 tickets for each show for out-of-town subscribers who, surprisingly, paid us back for the money we laid out. (Thank you!)

This year’s show was a little different than last year’s because it was recorded for a live album to be released this summer on Giant Records.

From what we hear, everyone involved in the production of the live album (including Elliot Scheiner, who worked on previous Dan albums) are thrilled with the sound quality of the recordings. Although a couple of artists were called back during mixing to do a few overdubs, everything sounds great, especially the Steely tunes. Donald, who was especially pleased with the results, is contemplating releasing the live version Of “Pretzel Logic” as the first single for radio play.

As we speak, the mixing of the record is finished. Most of the performances used on the album were taken from Saturday night’s show, with the exception of Charles Brown, whose Friday night performance was used.

Originally, the show was also supposed to be filmed for home video. Unfortunately, this idea was scrapped because of budget constraints.

The show started promptly at 8:00 p.m. with Jeff Young and The Youngsters and the hot backup singers Mindy Jostyn, Dian Sorel and Ula Hedwig with the Youngsters’ original tune, “Working My Way Downtown.” Then, Donald took the stage as the band swung into “Madison Time.” Phoebe Snow and Michael McDonald joined the group on stage with a rousing rendition of “Knock On Wood.” Not losing a step, Fagen followed with “Home At Last.” With these great songs launching the show, the audience knew they were in for a treat. Boz Scaggs was then introduced and went into one of his big hits “Lowdown” which gave Youngster’s bassist Lincoln Schleifer a chance to strut his stuff. Boz then followed with Gamble and Huff’s “Drowning In The Sea Of Love.” (We liked Donald’s Lone Star version better).

The ladies seemed to enjoy the next song “Minute By Minute” as they swooned over McDoobie’s looks and haunting tenor voice. Phoebe then shook the crowd with her pyrotechnic performance of “Shaky Ground” followed by “At Last.” The versatile organ player Jeff Young joined percussionist Phil Hamilton and shared vocals on Sam Cooke’s “Soothe Me.” Fagen then closed the first set with Steely Dan’s “Black Friday.”

After a twenty-five minute intermission, Charles Brown, the great blues pianist, took the stage and treated the crowd to “Quick Sand,” “Driftin’ Blues,” and, from his new release All My Life, “Joyce’s Boogie” featuring some tasty guitar work from his guitarman Danny Caron. Then, the surprise guests for the evening, the Brigati Brothers from The Rascals, added a nice touch to the extravaganza with “Good Lovin’,” “Groovin’,” and “How Can I Be Sure.” Another surprise was Jimmy Vivino who served as the Brigati’s musical director and guitar player. Since we’ve seen Jimmy playing alongside Donald at several NYC clubs in the past year, it was great to see him again on this big night.

McDonald then stunned the audience with an unbelievable version of Jackie Wilson’s “Lonely Teardrops,” which Fagen remarked could only be successfully attempted by his former bandmate.

We knew the night wouldn’t be complete without excited Dan fans yelling for their obscure and not-so-obscure Dan titles. As Donald pretended not to hear them and stuck to the song list, their howls were silenced as Donald started into “Chain Lightning.” As the song progressed, a strange man appeared on stage, like an uninvited guest. He gave the affair on-stage the once-over and then proceed to wow the crowd (and the, band) by joining in on the “vanished trumpet.” This is tough to describe since there was no trumpet; he cupped his hands, and then trumpet sounds mysteriously appeared. Afterwards the crowd realized this guy was not some bum off the street; his name is Bob Gurland.

Mindy Jostyn then followed with her steamy version of “That’s When It Hurts” and sent many men home to a cold shower.

Boz then did the duet “Love Is Strange” with Dian Sorel while drummer Denny McDermott kept a funky, yet steady beat. McDonald then followed with Holland/Dozier/Holland’s “Little Darling.” Then the unmistakable opening of “Pretzel Logic” followed, as the Youngster’s hotshot guitarist Drew Zingg played the blues guitar keeping a close feel to the album version. Phoebe then set the house on fire with Ragavoy/Burn’s “Piece Of My Heart.”

And Donald saved the best for last, with a new song to his live collection, “Green Flower Street” from “The Nightfly.” The horn section featuring Cornelius Bumpus, Chris Anderson and John Hagen shined through this song while Jimmy Vivino performed the hip rhythm guitar part. Again, as throughout the show, Schleifer and McDermott kept the band’s engine running. And as the three girls sang “Lou Chang burns with rage,” you had to laugh as only Donald Fagen could get away with such a line.

The show encored with the Rascal’s feel-good hit “People Got To Be Free” as everyone (including Charles Brown who picked up the words quickly) joined in for the finale. What a night. We were so excited. And we just couldn’t hide it.

On the way out, we ran into “Metal Leg” subscriber Trevor Johnson who flew in from Manchester, England, just for the shows. We asked Trevor if the show was worth the trip. He said just seeing Donald live was enough for him and he would do it again in a second.

Live Appearances

When we last left off in late October, “Hades,” the small club in NYC where Donald had been making some regular guest appearances, had been shut down by the authorities. Not to be dissuaded, Jimmy Vivino moved his Little Big Band downtown twenty blocks to the world-famous comedy club Catch A Rising Star which had been looking to add a late night music show to its schedule. From the very start, the room just didn’t seem right and the vibe didn’t feel good. However, we did get one great show which will be known as “The U.S.O. Show” since it took place on the eve of Operation Desert Storm.

Again, Metal Leg subscribers had first-notice on the gig and jammed the room anticipating the great music that was to come. With the Beacbn Show less than two months away, this served as a warmup to future appearances by Donald. As the show was starting, keyboardist Jeff Young was running late, so Dr. John volunteered to sit in and did the “Wang Dang Doodle” with singer Catherine Russell. And, for you R.E.O. Speedwagon fans out there, lead singer Kevin (“Keep On Loving You”) Cronin made a surprise appearance and did a somewhat competent version of “Johnny Be Good.” He even danced with Phoebe Snow on the crowded stage. What a night! Donald donned a blue baseball cap a fan had tossed to the stage and appropriately did “Black Friday” as Saddam Hussein was dreaming of Victory. Mr. Hussein probably now wished he would have been in NYC at this “Mother Of All Shows.”

However, the Catch A Rising Star gig didn’t work out. So again, Jimmy hit the road. This time he moved crosstown to his current and more comfortable Tuesday night gig at The China Club at 75th and Broadway. This is where the live “Green Flower Street” debuted with Donald only rehearsing the song once earlier in the day with Jimmy’s band. Jimmy’s gig at The China Club has attracted even more great musicians as Hiram (“My Rival”) Bullock and Steve (“Walk Between The Raindrops”) Jordan joined Donald and Jimmy on stage for some blues tunes. Max Weinberg (ex-E Street Band), Randy (Walter’s Guitar Mentor) California, and Jenni (Todd Rundgren backup) Muldaur are others who have made guest appearances.

One funny night, while Bullock and Jordan were on stage with Fagen, Jimmy had announced that bass player extraordinaire Anthony Jackson was in the audience. Jimmy kept calling, over and over, for Anthony to join the crew on stage. The crowd was very excited since Jackson had played on some of their favorite Dan tunes. When there was no response from Jackson, Donald took over the mike and started calling for Scott LaFaro, and Jimmy Blanton, also famous bass players. They too, didn’t join them on stage, but at least they had an excuse — THEY’RE BOTH DEAD!!!

Jimmy’s band is building up quite a following on Tuesday nights at The China Club. His group has been playing some great new original tunes called “All Alone” and “Stone Soul Minute” along with classic R&B and soul songs. You should check these guys out. You might even catch a glimpse of the Nightfly himself … but you’ll never know for sure…

Becker Solo LP

Although the spotlight for the past few months has been on Walter’s production of Donald’s new solo album, we’ve found out that Walter is planning his first solo project. And, in a reversal of roles, Donald Fagen will be producing his debut effort. Becker had planned on doing a solo album, but never got around to it because of “…laziness and sloth and lethargy” as he put it to Musician magazine’s chief troublemaker Matt Resnicoff. “But I am trying to write with (an album) in mind now… I have some songs, some instrumentals that are pretty firmly (rooted) in the Disco/jazz/Spacefunk/Muzak vein.”

As far as Donald’s new record is concerned, apparently progress is being made. Walter is coming back to NY on May 9 to continue production of Donald’s new record. We hear that the goal is to finish the album by September (yeah, sure). If this is true, however, Walter might have to spend most of the summer in New York. Regardless, this will give Walter a chance to break-in Gary Katz’s and Donald’s new Upper East Side studio called River Sound. The time questions are crucial, though. Donald has been invited to do a “Rock & Soul Revue” at the Montreux Music Festival in July in Switzerland. And then, a northeast U.S. tour in late fall is also being pondered for the “Review.” If Donald decides to do both, can he finish his album in between these two events?

In a recent issue of Billboard, Walter and Donald talked about the recording process: Walter expressed “It is much easier to enter a project, after the songs have been written: All the hard work is really done, and you just book into some swank recording studio, find a comfortable chair, order some food, and start recording.” Fagen noted his dislike for the use of drum machines. “I’m insulted when I hear something and I know that for the drum track, and maybe a lot of the other instruments, someone just pushed a button and that’s what I’m hearing. I feel really manipulated by it.” Becker’s feeling are mixed: “A lot of records are technically well-recorded and well-produced; the quality of a lot of the stuff is excellent. But because of this preoccupation with sound and production, the content is often less interesting than it might be. In a lot of cases, there’s little or no content that I can discern, just a tremendous number of synth sounds. I try to avoid that.”

Well, talking about “new” CDs, a bootleg entitled “All Too Mobile Home” features the Steely Dan Live At The Record Plant performance of 3/20/74 with ten tracks including the unreleased title track. The CD is on the Scorpio label out of Italy. The inside cover identifies the keyboard player as Walter Fagen. Walter Becker is spelled right, though. The front cover is a painting of a dildo made up to look like one of those silver streak mobile homes. We don’t think Fagen and Becker are making any money off this, but what are bootlegs for anyway?

Now on the legitimate side, Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab has just released the 24k gold plated Ultradisc of Gaucho. This follows the previous Ultradisc release of Aja. Both gold discs are a marked improvement over the domestic MCA aluminum disc. You might want to check them out.

Walter’s production work can be heard on Bob Shepherd’s new Windham Hill release and Andy Laverne’s new Triloka release. Walter also will be producing Windham Hill artists Marty Krystall and John Beasley and expect further Triloka work also.

In Gary Katz news, his work with Paul Brady is finally out on Fontana records. Paul’s effort, Trick Or Treat features Katz regulars Jeff Porcaro, Paul Griffin and Elliot Randall. It’s a great album, you might want to pick it up. Unfortunately, the news on Rosie Vela’s followup to Zazu is not good. Apparently, her record company wants Rosie to make some changes to her songs, and she staunchly refuses their requests. Hopefully these problems will be resolved and we’ll hear something from this Texas-bred model/singer.

Gary, a real “feel merchant,” as Eric Stewart puts it, has also been tapped to produce the return of English supergroup 10cc at River Sound. Graham Gouldman adds that “working with Gary has just been fantastic.” When ML asked why they chose Gary to produce their comeback album, Eric replied, “As 10cc, we always produced our records ourselves, but on this new project, we decided to use Gary because of our love for the Steely Dan Records.”

A Steely Dan/10cc connection has been noted earlier in the February ’88 edition of Metal Leg. In a 1976 UK radio interview with Becker and Fagen, the following discussion took place:

Caller: “I want to ask them about an article I saw in The Melody Maker about 1 or 2 months back, which was comparing the state of English music with the state of American music, and it mentioned Steely Dan and compared them with 10cc and said that 10cc were better for some reasons. There was a response from Melody Maker’s readers the following week which rejected the article, and I wanted to know their feelings on the state of English music compared to American music.”

Walter Becker: “…I noticed there are a lot of English groups like 10cc, that seem to be getting into extended formats, kind of a delayed reaction to Yes and groups like that.”

Donald Fagen: “I really don’t think there’s too much comparison between, say, us and 10cc. I think they’re a very good band, but to me it sounds like they’re more in a McCartney-type bag than we are. At least we like to think we’re original in what we’re doing, and I hear a lot of Beatle echo from that band, although I think they’re very competent and quite good.”

Look for Donald to play some piano on the new 10cc album.

“Metal Leg”: The TV Show

The following is a transcription of a television interview with John Stix, the editor of Guitar For The Practicing Musician. Over Stix’s career, he has distinguished himself as one of the most knowledgeable writers on guitar playing and music in general. Since John has gotten to know Larry Carlton over the years, we couldn’t think of a better person to have on a segment of a late night talk show that aired in 1987 in New York and Los Angeles with Metal Leg editor Peter Fogel and the host of the show who wishes to remain anonymous:

Host: Let’s start this show off with John’s first thoughts on Larry Carlton.

John Stix: Interesting, interesting player. He began by watching television, loving Gene Autrey and Roy Rogers. And at a very young age, unlike most of us, he didn’t get into rock and roll. It was an album by Gerald Wilson called The Moment of Truth. The guitar player that inspired him Joe Pass. So he went from country music right into jazz. The only blues

album he had for a very long time his grandmother gave him, B.B. King: King of the Blues. Until he was 20, that was it. It was jazz and that one blues album.

Host: Somebody told me at The Bottom Line in New York City that “A Whole Lot Of Love” by Led Zeppelin was one of Larry Carlton’s big things when it hit.

Stix: Rock was happening very big when he finally jumped into it. It was full-blown and doing very, very well. And he mentioned to me as well that “A Whole Lot Of Love” by Zeppelin was something that stuck in his head. The sound of Cream came into the mix, so all of a sudden we have somebody that’s well-schooled and well-versed in the intricasies of jazz. He feels the passion and the simplicity of the blues and the fire of rock music. And it all melts together here.

Host: At the gig at the Bottom Line the other night, Larry treated the crowd to the opening bars of “Don’t Take Me Alive.” Charlie Lico, Larry’s manager, talked more to Pete Fogel about that.

Pete Fogel: Charlie told me he was trying to convince Larry into incorporating some Steely Dan melodies into his show since so many people at the gigs were yelling for Steely Dan songs. I think that was Larry’s first try and the crowd went nuts. (Turning To John) John, you were telling me about Robben Ford, an excellent guitar player. Robben was Larry’s inspiration for his first album by which everyone knows as “Larry Carlton … Mr. 335.” TelI us about that John…

Stix: For many, many years, Larry was doing studio work. He had played with The Crusaders. He was doing this for many years and he wanted to break out. He wanted to gain his own identity. Like most players, he was looking for input … outside input, and in this case, he got it from a wonderful guitar player Robben Ford. He (Carlton) thought “Wow, Robben is combining all the things that I would like to combine in being aggressive in my guitar playing, in making a melodic statement, putting a lot of feeling and power into it, and that really comes out on “Mr. 335.” On that particular album, out of all the records he did for Warner Brothers, that’s the one where he’ll say, “I was going for it all the way, I wasn’t thinking about listeners, I wasn’t thinking about pleasing musicians. I just wanted to put myself into fifth gear and push myself to the limit.” And like so many great players’ first albums, that became the standard. That’s the album that everybody holds up as… “Larry Carlton.”

Host: Larry Carlton did a lot of work with Steely Dan. You and I were out there, Pete. All you hear is “Steely Dan, Steely Dan!” coming from the crowd. (To John) What do you know about another Dan album?

Stix: It’s interesting to note that Walter Becker and Donald Fagen are working and there very well “may be” another Steely Dan album, if all goes well, and it has for over a year…

Host: And Larry Carlton will be on the record?

Stix: We don’t know. There are some interesting stories though.

Pete: I spoke with Larry last week and he hasn’t heard from Donald or Walter yet. They used Steve Khan a lot on the Gaucho album, but when Donald went out on his own, he used Larry as his main guitar player.

Host: Donald Fagen said something about Larry Carlton that you were telling me about, John — what an excellent technician he is, but also has the heart with the blues…

Stix: Yes, Lar said “With all Steely Dan albums, the soloists have to have the blues. They have to be able to feel it, and to play it.” And the album The Royal Scam is considered by many to be among the great guitar albums and great Steely Dan albums, of all time. And Walter Becker, as well, puts the reason that album is so important to guitarists is all because of Larry Carlton.

Pete: “Kid Charlemagne” really started off the record with a bang.

Stix: Absolutely. In fact, Larry will say that it was the highlight of his session career.

Host: I heard at one point in Larry’s career, he kinda wanted to step out of the guitar light, so to speak, and move into producing.

Stix: I think it was during the Sleepwalk period. He had a child, was very into his family life. He said, “Look, I’m sorta giving up on the guitar sweepstakes of being in the limelight and I just want to concentrate on being a producer. I also want to concentrate on being with my family.” And at the time, he produced The Gatlin Brothers, Bill Withers and he was also learning by producing himself. And then, as time went on, I spoke to him a short while ago and he said, “You know, John, no matter what, I now know, that the gift that Larry Carlton has is as a guitar player.” And so he has come back to it. And that is what Last Nite, the live album is all about. He felt that since the band was so hot, interestingly enough, he funded this album himself. He said “This band is great. I gotta get it down on wax. If somebody wants to put it out, fine. ‘Cause I think they will at some point.” So he did this because he loved it and then MCA, his record company, bought it after-the-fact.

Pete: John, Larry became famous with 335 guitar. And right now, Larry mentioned to me that he’s using the 335 as a spare. He hadn’t picked it up in over a year, until John said “I love the show, but how come you’re not using the 335 anymore?’ Well, the second show that night, Larry picked up the 335, blew the dust off of it, and mentioned the conversation with John. Why did he lay off the 335? He’s now using a Valley Arts guitar.

Stix: Well, he discovered two things: One, that the 335 had a very low, bassy sound. He found himself playing high up on the neck. He said, “Hey, I’m not using the whole range of my instrument.” Two, he picked up a guitar from a friend of his, Dean Park, also a fine player from L.A…

Pete: He played on “Rose Darling” on Katy Lied…

Stix: Yes, that’s right. And Carlton said, “Boy, this neck feels like a flyweight. I could do anything I want with this. Why am I struggling to push the notes out. I can zip and run.” And somehow he switched guitars.

Host: To a lot of people, he still is “Mr. 335″…

Stix: He still is “Mr. 335.” In fact, I told him, “Larry, you come out, you don’t play this 335 guitar that you’re so famous for. It’s like the Jolly Green Giant coming out and he’s yellow. If you pick up that 335, you’re gonna get a standing ovation without doing anything.”

Host: Let’s talk alout Larry’s record, Alone, But Never Alone.

Stix: That brought a whole new audience to Larry and it was really based on playing the acoustic guitar which was something he has never done, never thought of before. Like always he composed the songs the night before the sessions…

Host: I can’t believe that…

Pete: Larry is something else. You know, the tone, technique, ear and imagination — he plays with his heart, and that’s why Larry Carlton is the best player around.

Stix: And if you want to hear him unadorned, playing melodies, Alone, But Never Alone is the album to do it. And I would say if Larry pointed to one person for melody, he would point to John Coltrane and specifically an album called Ballads. And Larry’s often said to me, “If you can, as a player, take a song … take a Beatles song, just play the melody and make it sing … and make it go to somebody’s heart … don’t make it a melody on the way to a solo… and make it as heartfelt as you can.” That’s on that acoustic album and it brought a lot of people to Larry as a brand new audience.

Larry Carlton on Steely Dan

The following questions and answers have been compiled through the years and give us Carlton’s feedback on recording with Becker and Fagen:

Q: How did you come to record with Steely Dan, one of the most revered bands as far as the guitar players are concerned…

Larry Carlton: Oh, definitely! I started with the Katy Lied album. They had everything cut except for one song, and they’d tried virtually every guitar player in town except me. I think they thought I was a jazzer, because of my Crusaders work, and I think they also thought, that I had too much of an identifiable sound. Anyway, prior to this I had arranged an album for Joan Baez, called Diamonds and Rust, and it was a gold album here. Anyway, I got this call to do an overdubbed rhythm part for Steely Dan and when I got there the guy said, “Man, we’ve been trying everything and everybody and we can’t find a feel for this tune. You’re the last guy — it’s ready to mix.” So we started running it and what I played was exactly what they wanted. So we did the take and I was out of there in an hour, and that started my association with the guys in Steely Dan. I asked them later how come they never called me before that, how come they used everybody else in town and what made them finally call me, Walter Becker said ‘I’m not a Joan Baez fan at all, but when I heard what you could do with the music of somebody I don’t like; I thought this guy’s got something, we should check him out.’ So that was the start of it.

Then for the next record which was The Royal Scam, they sent me the demo tapes and had me map out the charts for them and fill in little bass lines that Walter didn’t put in. I’m not crazy about what I played there, but I was kind of their organizer; I could never take credit for arranging Steely Dan! People have seen that credit for me, but they just needed somebody to be their liaison in the studio, between them and the other players.

Q: I recently met Elliot Randall and he finally told me which tracks be had played on, “Green Earrings,” and “Sign In Stranger” which I had always thought were you. They don’t credit the musicians for which tracks they played on, so can you remember them — apart from “Kid Charlemagne,” which we all know about?

LC: No, if I listened to it I could tell you … I know I played on all the basic tracks. I know Dean (Parks) played on the one with the talk box…

Q: “Haitian Divorce?”

LC: Right, he did it straight and Walter went back later and processed it (Added the “Voice Box” effect) later.

Q: Just for the record, the “Kid Charlemagne” solo, was that a first take all the way through?

LC: It was two takes, two parts. I did the first part and we backed it up to the middle section and then punched in from there.

Q: Your tune “Room 335” is a obviously a cop from “Peg”? Tell us more.

LC: It’s the same chord sequence, the opening.

Q: Was the production of that whole album influenced by Steely Dan?

LC: No, I’d have to say that it wasn’t. On their records they cut their tracks spending four, five or six days for one tune, and they picked them apart. On ours, we played it until we got a performance and that was it — even with imperfections — because it felt so good.

Q: By the time they got to Gaucho you were just about the only guitar player Steely Dan were using.

LC: Yeah, except they went back to New York and decided to try something different and I wasn’t actually involved in the Gaucho album. But one of their masters got erased, so they pulled out one of the outtakes, which was “Third World Man,” either from Aja or The Royal Scam. So I was as surprised as everybody else when I picked up Billboard and it said, “…and a wonderful guitar solo by Larry Carlton on the Gaucho album…” But they’d just pulled it out of the can and remixed it because one of their masters had been erased — Then there’s Donald’s album … that was fun. I did seven of the solos or something on that album.

Q: That record took a ridiculous time to make, didn’t it?

LC: To the best of my knowledge it took — and I knew it for sure at one time — a year and a half and a million and a half dollars for The Nightfly — I think! And it took me four days to do my part.

Q: Were those four days spread out over a long time?

LC: No, I flew to New York, stayed five days and worked four, and in a few hours I was home. Got a good record as well! I love that record.

Q: Did you feel relaxed working with Steely Dan, or was it an intimidating experience even for someone with your experience in the studio?

LC: No, I just knew that I loved their music. It was totally relaxed.

When John Stix was with Guitar World in 1981, he asked Larry some detailed questions on working on The Royal Scam and on Donald and Walter in general.

Stix: Steely Dan’s Royal Scam is one of the finest albums for contemporary electric guitar that has come out in the last decade. And my vote for the best solo on the album goes to your playing on “Kid Charlemagne.”

LC: It’s my claim to fame (he chuckles). I did maybe two hours worth of solos that we didn’t keep. Then I played the first half of the intro, which they loved, so they kept that. I punched in for the second half. So it was done in two parts and the solo that fades out in the end was done in one pass.

Stix: Do Becker and Fagen demand more of you than the usual session, and if so do you put out more for them?

LC: Their demands are so high. It was grueling going through The Royal Scam album because I was so heavily involved in the tracks and the charts. We cut tunes six or seven times with different drummers. I was pretty fed up and thinking, ‘Are those guys ever going to be happy with what I do?’ When I heard the record, then I realized that I wasn’t the person that should be judging them at all. I knew how hard they worked on it, but I saw why. It was just outstanding.

Stix: Is “Charlemagne” the high point of your career as a session man?

LC: Probably so. I can’t think of anything else that I still like to listen to as strongly as that.

Larry Carlton biography

Native of Torrance, California. Studied with Slim Edwards for some eight years. He was a music major of Los Angeles Harbor College from 1966 to 1968 and a music major at California State at Long Beach from 1968-1970. During these last years Larry played with Bill Eliot. He toured with The Fifth Dimension and recorded his first solo album. In December of 1969, Larry become the musical director of a children’s show on NBC. He even performed on-camera as a costar “Larry Guitar” as well as writing much of the music used on the show. Since 1970 Carlton has played on literally thousands of recording sessions, TV shows, movies and commercial jingles. In 1973 he joined The Crusaders but became known to many of his fans through his acclaimed work with Steely Dan in the mid-to-late ’70s. He also won a Grammy with Mike Post for the theme song to “Hill Street Blues.” In 1988, he was almost killed in a random shooting outside his California home, but has since recovered fully and is continuing to treat the music world with his heartfelt guitar playing.

Gaucho-era interview with the Dan

This interview with Mary Turner was broadcast in the latter part of 1980 after the release of Gaucho and Fagen and Becker were in particularly good form with their repartee. However, little did we or Mary Turner know at the time that Donald and Walter were about to face up to the inevitable fact that their partnership was in the process of dissolving even as they spoke. Within six months, Steely Dan would be no more.

Mary Turner: Hi, I’m Mary Turner and with me are Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, the guys that put together Steely Dan. They met in college in upstate New York and started writing songs together, but their lyrics and harmonies were too strange for the pop scene of the late ’60s so they paid the rent by playing in the band with Jay and the Americans. Did you go on the road with them?

Walter Becker: Yes.

MT: Was it fun?

WB: Sometimes it was fun. Depending on where we went.

Donald Fagen: Tampa was foul that summer, wasn’t it?

WB: So was Waldorf, Maryland.

DF: Waldorf, Maryland was no fun either.

WB: Stardust Motel. Remember the time they were playing up in Queens and Jay got subpoenaed. That was no fun.

DF: That’s right, the guy with the gun. That was terrible.

WB: He was backstage, he was subpoenaed, that’s a whole other story.

DF: We don’t want to get into that, if you wanna know the truth, because we could end up with a horse’s head in our bed.

WB: I used to look forward to playing. We had hopped up their songs considerably harmonically and rhythmically, so that it was more fun for us to play.

DF: Spreem.

WB: We had modernized their sound, and I used to look forward to doing it and, of course, it paid the rent and we would work for like two, three weekends a month.

DF: I think that was the best band we were ever in.

WB: The nice thing about that band was that we were in the band and there were four guys in suits in front of us.

DF: Yeah, I mean, we couldn’t play shit, but were were in the band. Ivy divy, pashoo pashois. It was nice. Nice.

WB: It was like being part of the Four Tops. We didn’t look at their faces, we just…

DF: They had uniforms and things, I remember the guy who ran the Seven Seas Lounge at the Newport Hotel in Miami Beach used to complain about the way the band dressed, because Jay and the Americans looked really swell, but we were always not quite so natty.

MT: Then did you step right out of being in Jay and the Americans into being staff writers at ABC?

DF: Well, it was a long step because it was from New York to California; it was a doozy, so to speak.

WB: Prior to that step we had been standing in a pile of legal entanglements (chuckling). That made it a very tough step.

DF: We had to call our attorney. But it all worked out for the best.

WB: Yeah, ’cause we weren’t really doing anything particularly earthshaking musically. I mean, there’s only so much you can do with “Only In America.”

DF: Mainly we used to ride bikes in Prospect Park, that sort of thing.

WB: We were writing a lot but we had no vehicle for them, and Jay wasn’t interested. He thought we were amusing. Jay was very tolerant towards us, as I think he indicated when he told Rolling Stone we were a couple of cocksuckers.

MT: (Laughing) A true fondness for you.

WB: Yeah, he really did like us. When we were offered a job writing songs and doing something besides playing “Only In America,” it seemed like a nice idea for a change. Plus it would pay us whether he had a club gig or not.

MT: Donald and Walter got to LA through an old New York friend, Gary Katz, who’d just gotten a job for ABC Records.

WB: When Gary got to LA, the first thing he did after he got his job he said “I’ll put my job on the line for these guys.” So they hired us; they figured, what the hell.

DF: And he still had his blue bathrobe on, too.

WB: (laughing) And his credit card. But they were very thrilled with Gary. The situation then was that ABC had the Mamas and the Papas, Barry MacGuire…

DF: Three Dog Night…

WB: …the Grass Roots, Bobby Vinton, Tommy Roe, stuff like that. They didn’t have a big underground thing going. Gary had a certain type of moustache that convinced them that he would be a good underground producer.

DF: Right, we were like the Cat Boy and All-Night News Boys of ABC Records.

WB: Yeah, we were the Grateful Dead of Beverly Boulevard. Very weird.

MT: Little by little they got a band together to play their songs. One of their guitarists they chose was Jeff Baxter.

Jeff Baxter: Here’s what happened. Gary got a job as a staff producer at ABC Records. Howard Stark and Jay Lasker were running the joint, both really good guys. And Gary signed Donald and Walter as staff songwriters ’cause at the time Steve Barri was staff there and there was a real use for those tunes. ‘Course they didn’t know what kind of tunes they were gonna get and to quote Jay Lasker, he said, “Gary, you didn’t tell me that I was gonna get a band with these two dummies.”

So we had a band. Jay had a band. And he had to go out and buy a PA system, so we could rehearse in one of the storerooms. It was great, it was like being in a family. I remember when Howard Stark gave me a check for a thousand bucks. I went nuts! Wow! And he looked at me real serious and said, “Yeah, get yourself a nice apartment and find yourself a nice girl and put some money in the bank.” I was flabbergasted. I said thank you very much.

But that was the attitude, they sort of took care of us, though they couldn’t really understand what was going on. As long as Dennis Lavinthal said it was OK, then we were gonna do it. And we had a little room upstairs, an abandoned office where we brought a PA system and set up all our stuff. We did it just like a band — we learned a bunch of tunes and then we went out to this club and played. It was really nice.

MT: The band they finally came up with had Donald Fagen on most keyboards, Walter Becker on bass, Jeff Baxter and Denny Dias on guitars, Jim Hodder on drums and Dave Palmer singing lead on some songs. Keeping it all together was producer Gary Katz. The old office they worked in was no more than fifteen feet square, it had no windows, white tile on the ceiling and bright fluorescent fights, and the only time they could have rehearsals was at night.

JB: They’d start around six ’cause I was working at repairing guitars and customizing them for people and we couldn’t practice in the daytime anyway ’cause it was 9 to 5 in the office. So we’d go to our abandoned office around six ‘o clock with some sandwiches and rehearse until really late. And I’d drive back in my ’68 Ford Torino that I bought some nasty insides for and Donald would follow me ’cause Donald liked the way the car looked from the back. I had it painted wineberg and metal flake.

MT: The big success of “Do It Again” came as quite a surprise, and the new band had to go out on the road. So here’s this bunch of guys who’d kicked around pop music for years; they get it together in an abandoned office at ABC Records and rehearse their music with strange lyrics. They make an album, put it out and whammo it’s a hit. How’d they react?

JB: Went nuts. We started doing gigs. Ooooeee! Went on the road. On the road. Steely Dan. We had two road guys — Warren Wallace and John Fahey. They looked a lot better than the band. As a matter of fact, we got panned at the Whisky A Go Go our first gig ’cause we didn’t look good. The reviewer said that he wasn’t sure about the music, (laughing) but he definitely knew we were the ugliest band he ever saw. So now we figured out what the LA music scene was like and decided we would take our music and go someplace else.

So we took our little traveling circus around and we played gigs and it was really good. We took this little show on the road and played a lot of places and everybody really liked us. I was amazed, especially in Texas. I couldn’t figure that out. ‘Cause the band that would open for us would be unbelievably raunchy and funky and loud and boogieing, and we get on and — although I guess we did have that quality — every once in a while we could really crank it up and rock and roll. ‘Cause basically everybody liked to rock and roll. As much as everybody loves jazz — and we all love to play that kind of music — there’s nothing like rock and roll for your soul.

(Plays “Reelin’ in the Years”)

JB: The songs were great, and there was real dedication in the band. Everybody really wanted to play the best that they could and they always worked hard at it. And because everybody loved to solo — and because there were good soloists in the band — there was always room to solo. So we’d do a nice, tight piece and you’d be playing for about a minute and forty seconds, and then you’d go roaring into a set of changes, burn your brains out, get back into a solid groove and that to me … People used to always look at us like there was something wrong with us — not wrong with us — something different, you know, because they couldn’t believe you could stuff that much music into such a short space. I remember we used to open with “Bodhisattva” — that’s on the flip side of the Steely Dan single — at the Santa Monica Civic — and there was so much happening in that song all the time, even when it didn’t sound like it. And it got down to the point where Denny and I were getting down to just even the percussive things — hitting on the guitar, just getting it right. It was wonderful.

(Plays “Boddisattva”)

JB: You know, I wish I could tell you some stories, but I’m saving some of ’em, some great stuff. Oh yeah, touring? (Chuckling to himself) Now this was a touring band — this band knew how to tour. It was silly. The whole band was silly. We used to do some great tours; we used to open for The Doobie Brothers, Rare Earth, Sha Na Na. We always went on the road with real fun guys, and we had Dinky Dawson who was doing the PA … and the guy who mixed our monitors was interesting. He mixed them so he could hear real well, and he’d get a nice sound that he liked and he’d take his violin out and play with us, throughout the set. Everything was really …. a little, kind of … shaky.

MT: So touring was real tough for you guys, huh?

DF: Yeah, I often crumble. Very quickly.

WB: Donald has to sing and that’s a tough thing to do. If you get a cold, you still have to sing every night. I’ve seen that happen to almost everybody that I’ve worked with — that I’ve been on the road with. They have to sing every night and naturally their voices begin to…

DF: I’ve never had any voice training, nor am I inclined to take any and…

WB: It’s like football players and their knees; it’s just a matter of time.

MT: So it’s not like you hate the rigors of the road?

DF: Well, I dislike the rigors of the road. As I say when we were with Jay, you had four guys fronting the operation with the uniforms on, that was OK with me. I enjoyed it.

WB: You were still sick a lot.

DF: Yeah, I was sick a lot, but it was OK. It’s just I don’t like to front a band, you know, have to talk to the audience, tell jokes.

WB: We were gonna get matchbooks and have a picture of Donald with the legend: Can you sing like this man? So we could get another lead singer. He’d just have to play the piano.

DF: I don’t like the jock atmosphere of a traveling rock and roll band either…

WB: It’s corny…

DF: It’s corny, boring and silly.

(Plays “Pretzel Logic”)

MT: By the mid-’70s, Steely Dan was changing. They’d started out as a group of guys building a band, but with each album, Donald and Walter brought in outside players to handle special parts. Then Jeff Baxter left to join The Doobie Brothers, he was followed by background singer Michael McDonald. What was going on? Here’s Steely Dan’s producer, Gary Katz.

Gary Katz: Donald and Walter’s music was evolving and it was opening into more sophisticated and sort of an expansion of their old style. And they wanted the freedom to utilize as many styled players as fit the tunes that were then starting to be written. Jeffrey had an opportunity at that time ’cause he had been playing off and on with The Doobie Brothers as a guest, and to be a full-time member afforded him the opportunity to be on the road a lot, which he enjoys. He wasn’t getting that with us and it didn’t appear that he would. So he had the chance to do something that he liked and obviously, Michael had that opportunity, too. With Steely Dan, Mike was a background singer which was an ultimate waste of talent. There was no big blow-up or argument. It never happened.

(Plays “Dr. Wu”)

GK: It’s not a written chart for each player because the purpose of having the really good players that we enjoy working with is to be able to get their musicality that we hired them for. So they have this general idea of the song and they have a chord sheet in front of them, but I want their expression and their ideas — as Donald and Walter do. So it’s not like a rigid chart to say the least, but it is written out so that they know where it goes from section to section and what chords and so forth. Yeah, in that sense, it’s structured out before we go into the studio.

We do a demo, and we decide whether we like the way the song lays, if so, we write up chord sheets for that, if not, we make an adjustment, then write up a chord sheet. And when the players come in, we have this little ugly demo with just terrible electric piano sound and Donald’s sort-of singing, and maybe Walter playing the bass line and chord sheets, and it’s pretty clear what we’re looking for. And then it’s a process of going out and laying it down and hacking it out and getting what you like.

(Plays “Kid Charlemagne”)

MT: A lot of bands make records quickly. They go into a studio and play, but Steely Dan sessions are long and sometimes difficult because Donald, Walter and Gary Katz are very demanding.

GK: You work with some people and you know what you can get and what you can’t in anything you do. I know what a certain performance, as Donald and Walter do, what a certain song can sound like ’cause we’ve had it now enough times either on tape or by ourselves or by a rhythm track to relate to. We know what a song can sound like and if it’s short of that, it’s not good yet. So yes, it’s boring on the 25th take, but there’s a light at the end of the tunnel, so to speak, because we know what it will sound like and we like that — I like that a lot, so I can endure it but it is boring sometimes. And very difficult for the performer if you continue to do it and wanting it better than he just did.

(Plays “Don’t Take Me Alive”)

MT: Does Gary enter into the creative process with you or do you get everything written so you know what you’re gonna do and go to Gary and go into the studio?

DF: Yeah, basically that’s what it is. Everything’s prepared by us and when we go into the studio, Gary’s function is mainly to supervise things, make phone calls, that sort of thing. (Mary Turner laughs)

WB: That’s not entirely fair.

DF: No, he’s a third ear. Walter and I each have one ear apiece, I don’t know if the public knows that, we both had accidents in our youth and Gary has a third one.

WB: A third ear, that’s great. And I hope he’ll remember that one.

MT: Siamese ears.

DF: If you please, or if you don’t please.

WB: Actually, you can’t see Gary’s ears because of his hair, but if you could, you’d know what we were talking about.

(Plays “Peg”)

WB: No, the way we work with Gary, we have this kind of gestalt…

DF: Yeah, that’s a nice word. You could use weltanschaung, but gestalt will do.

WB: What was I saying? German lesson? We have a kind of difficult to describe…

DF: This is a very German interview.

WB: Very Teutonic. So that we arrive at decisions in a very … you know, we know what we’re all thinking and we have the same objectives, pretty much so that not too many really bad discrepancies arise, because one person wants to go this way and someone wants to go that way.

MT: Are you pretty much in accord in your thinking then when you’re in the studio?

WB: Not bad, not bad at all. I mean we’ve been…

DF: We have a few disagreements once in a while, but you know we’ve been together for ten years and it’s been pretty smooth considering.

WB: What we usually do is we’ll try it one way and try it another way and it’s not hard to tell what works. It’s sometimes hard to say in advance what’s gonna work. That can be a problem, but we’ve gotten to be fairly extravagant in our recording techniques, so if something doesn’t come out the way we had it in mind, we just do it repeatedly until we think that either it’s a bad idea in the first place or it works out for us.

DF: Get it Tuesday and do it Thursday.

WB: We recorded “Peg” maybe five or six times with five or six different bands.

DF: Yes, that’s a good thing about not having a band because in effect you have a lot of bands.

MT: So on one album it could be ten different bands, huh?

WB: I think there was five different drummers on Aja. There must have been five different bands on Aja, on certain cuts?

DF: Uh huh.

MT: When you have a tune and you’re ready to cut it, do you hear it in your head and go, “This requires Bernard Purdie, get him on the phone?”

WB: We make up lists of tunes and lists of who we think they require and then lists of who we’re gonna get if we can’t get so and so.

DF: And if it doesn’t work, then we’ll do it Thursday, as I say, with another band.

(Plays “Deacon Blues”)

GK: (Referring to Pete Christlieb, the “Deacon Blues” saxophone soloist) He came about because we liked the saxophone player on the Tonight Show and we found out who it was, that’s how exactly that happened. And we kept on hearing this one guy who was great, but never could figure out in the band who it was, so we called … We had one player come down thinking it was him, and when it wasn’t, we called the other one and it was Pete and he was great. And he played on other things, he played on “FM” as well. Pete’s a free spirit, there’s not much controlling Pete, which is exactly what we want. So you just run the music by him and he blows his brains out and it’s great. He’s just a great player. That is a very uninhibited session with Pete because he just wants to play, he just wants to hear it and he’ll play it. And we like that spontaneity.

(Plays “Hey Nineteen”)

MT: Making a Steely Dan album involves a lot more than just setting up tape machines and microphones. Here’s Dick LaPalm, head of The Village Recorder, where they did Aja.

Dick LaPalm: When you’re dealing with people as creative as Steely Dan, the atmosphere itself has to be conducive to creativity. We know the kind of cookies that Gary Katz, their producer, prefers and you can be sure we know when he’s coming in, we’re gonna have a lot of chocolate whatever they are. I know that Roger Nichols, their executive engineer, loves “Good ‘n’ Plenty,” you know what they are? Little candies? Stock the refrigerator with “Dr. Brown”(soda), you try to make it as comfortable as … you leave them alone. And let them do what they have to do, and if there’s a problem, cover it for them as easily as you can. We try to keep the creative juices going all the time by anticipating a possible breakdown with equipment.

MT: And the answer isn’t always conventional.

DL: We were having a problem with the right speaker, that entire night, yes and no. It would work for 15 minutes and start cutting out, and in the end, it got to the point where we gotta do something so Gary Katz came up with the best idea. He picked up a can of cola and he just threw it at the speaker and it worked — they didn’t have a problem from that moment on. The next day, someone came in and said, “Dick, the Valencia cabinet on the 604NA is broken and the grill is cracked. What happened?” Well, someone in the Steely Dan session — we think it was Gary — and someone said, “No, it was probably Walter.” They broke the cabinet but the speaker worked from that moment on and everyone said, “Wow, isn’t that wonderful?” So you repair the speaker cabinet. Again, the important thing is keep the creative juices flowing.

(Plays “Aja”)

MT: Your lyrics are always really good, but they’re also sometimes very hard to follow.

WB: We’re very much concerned with the sound of the words and the music. There are many instances when we’re writing lyrics when we’ll sacrifice literal meaning or linear storytelling effects for sound effects.

DF: Yeah, we get a lot of flack about that actually. They say it’s hard to follow.

WB: That’s the way we’ve been writing songs for a long time and I think that…

DF: I think, we’ve gotten to the point where we rarely sacrifice literal meaning for the sound of the phonemes. I think we’ve come to a point where we can compromise and come up with a lyric that’s both meaningful and poetic as you will, or as you won’t.

(Plays “Babylon Sisters”)

DF: It is rock and roff, and if you just get too serious with it, then it s going to be pretentious.

MT: Do you have fun with it still?

DF: Yeah.

WB: Oh, yeah, that’s one of the nice things about rock and roll, it’s a very light-hearted thing at heart — at the center of it — and I think most people who forget that come up with some of the most ponderous music I’ve ever heard in my life. It’s really dreary-sounding stuff that happens when people get away from that basic idea that it is music that’s designed to have an infectious beat. I would never describe our music as anything but rock and roff because of the rhythms that we use. It’s a very propulsive, jubilant thing, and that happens to let you get away with certain types of black humor that would normally be oppressive to some people. I understand that some people are cheerier than other people but I don’t care.

(Plays “Hey Nineteen”)

MT: Some critics have said that using all those outside studio musicians takes away all the excitement of rock and roll.

WB: Well, that’s a critical point of view and has to do with the belief that the great rock and roll is made by some primeval swamp savages mysteriously equipped with electric guitars.

DF: Who all live together.

WB- Right, they crawl out of the marsh and they can hardly speak any English and they come in and record “Hound Dog” and that kind of thing, which is not true. A surprising number of your rock and roll records that people think of as being groups are actually the same studio musicians.

DF: They bring in firemen if they need’em.

WB: I mean studio musicians are studio musicians in the first place because of their tremendous facility as musicians, by and large.

DF: And also when we work with these musicians, they know they’re not gonna get a three chord commercial for “Uncle Ben’s Rice” or something. They’re gonna have some challenging progressions and some interesting rhythms to play and they know we’re looking for an atmosphere for each tune. We’re looking for them to come up with parts to cooperate with us, help us with the arrangement and take part in the making of the record, and because of that, they do a bang-up job which they probably don’t do all day long ’cause they work nine hours a day. As long as we’re together — just the two of us — and we don’t have a working band, we’re never going to have the kind of unified group sound that say The Band had for those years, or The Rolling Stones. It’s a different kind of thing and I think we accept that. I think we look to our writing and arranging to keep a unified style ’cause we don’t have a band.

(Plays “Time Out Of Mind”)

WB: I never doubted this sort of thing would catch on…

DF: No, musically we’re working with basic pop song forms, though we may distort them, they’re still basic forms that are derived from a balanced structure that people have been listening to for years. The popular songs of the ’30s and ’40s, we use those structures and I guess that was originally derived from sonata form or something, and basically you have two themes, one which is repeated several times in a recapitulation and so on. We’re pretty traditional as far as that goes and I think that’s the reason for the popularity of it, aside from, of course, our own doubtful genius.

WB: It can’t be all sweetness and light either. I’d like to go on record as saying that. I think by combining disparate elements, we often come up with something that’ll appeal to a lot of people.

DF: We like to use something old, something new, something borrowed and something blue.

WB: In B flat.

(Plays “FM” to close)

Only A Fool Would Say That

Review: “The Fall of Steely Dan”

The following review by Ken Emerson appeared in the October 18, 1977 issue of The Boston Phoenix. Mr. Emerson apparently didn’t seem to like the Aja album.

Steely Dan have always delighted in inscrutability, refusing with an elitist sneer to be fully intelligible to “hoi polloi.” Yet “Deacon Blues,” the most puzzling song on their new record, Aja (ABC), seems enigmatic inadvertently. It’s not a matter of mystifying juxtapositions here — of “bad sneakers and a Pina Colada/My friend” — but of where Walter Becker and Donald Fagen stand in relation to the song’s narrator, who aspires to the romantic dissipation of the jazz musician’s life. Are they scornful of his naive vow to “play just what I feel,” of his simple dream of “Sharing the things we know and love/With those of my kind”? And how are we to take “I cried when I wrote this song”? Whose tears are these? Are Becker and Fagen trying to be, of all things, sincere? And are they capable of it?

Though these questions are unanswerable, they point to the problematic nature of Aja, an album whose lyrics are preoccupied with home and with where (if anywhere) one belongs. And the record is Steely Dan’s first failure because Becker and Fagen have lost their arrogant sense of place and purpose.

There was a time when no American rock band mattered more than Steely Dan, for they did as much as anyone to drag pop music, kicking and screaming, into the ’70s. They did it by amassing a devastating critique of the sensibility of the ’60s and by proffering their own as infinitely more sensible. And, for a while, it seemed so.

Consider, for instance, their all-out attack on the concept of freedom, that rallying cry of pop music and youth culture in the ’60s which was amplified by an expanding economy and the baby-boom generation’s strength in numbers. The Dan put it bluntly on their very first album in “Only a Fool Would Say That”:

I heard it was you

Talkin ’bout a world

Where all is free

It just couldn’t be

And only a fool would say that.

They came bearing George Santayana’s bad tidings (from his Classic Liberty): “Any day it may come over us again that our modern liberty to drift in the dark is the most terrible negation of freedom.”

According to Becker and Fagen, it wasn’t the Establishment, our parents or our presidents that imprisoned pop’s white, middle-class audience. Instead we were (are) the victims of our own obsessions, they said, of the “perversities” for which Steely Dan’s lyrics have been so notorious. Becker and Fagen compiled a portrait (perhaps a shooting) gallery of compulsives: the gambler in “Do It Again”; the man who couldn’t say no to the rich woman’s sexual demands (“I foresee terrible trouble/And I stay here just the same”) in “Dirty Work”; the cornered psychotic (“I hear my inside/The mechanized hum of another world”) in “Don’t Take Me Alive’; the Randy Newman nut who was “never gonna do it/Without the fez on” in “The Fez.” None of these people could control himself, nor could very many others in Steely Dan’s underworld of mechanistic mentalities. Small wonder that one of their favorite words was “zombie.”

What turned many of these characters into zombies was precisely what the ’60s celebrated: the freedom to fuck and take drugs. With few exceptions (“Rose Darling” and, perhaps, “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” and “Any Major Dude Will Tell You,” which may or may not be addressed to women), Steely Dan’s lyrics have been violently misogynistic. That Becker and Fagen named their group after a dildo is apt, for many of the songs (“Fire In The Hole,” for instance) have described the perils of intimacy with women. Even their early album titles — Can’t Buy A Thrill, Countdown To Ecstasy — suggested that orgasms were strictly mechanical or couldn’t be had for love nor money. “Torture (was) the main attraction” of the females in Steely Dan’s songs: “Well I did not think the girl/Could be so cruel.” They habitually deceived (“Then you love a little wild one/And she brings you only sorrow”), yet they were dangerously habit-forming (“All the time you know she’s smiling/You’ll be on your knees tomorrow”). When Fagen sang, “I fear the monkey in your soul,” he (and/or the character) may have been addressing a woman who was a junkie, but he was also afraid of his addiction to her, the monkey in almost everyone’s soul. Drugs and another substitute phallus, the syringe, also pervaded Steely Dan’s music and debilitated their users. Like gambling, also a persistent image, dope offered only a fleeting illusion of freedom. And a gun, yet another sexual symbol on which Steely Dan’s lyrics were fixated, didn’t do much good, either. Unlike Californian neighbors (such as The Eagles) who romanticized outlaws’ flings with freedom, Becker and Fagen portrayed the gunman as a deadly schlepp:

When you’re born to play the fool

And you seen all the Western movies

Weren’t you the one who does it wrong?

…With a gun, with a gun

You will be what you are just the same…

To twist “Reelin’ In The Years” out of context, the “everlasting summer” of the ’60s was “fading fast” when Steely Dan began writing the decade’s obit in 1972. Many explanations of that demise have long been cliches: Altamont, the destructiveness of drugs, the dashing of revolutionary hopes, the belated realization that rock was simply another commodity in a capitalist economy, the entry of its audience into the adult work force just as that economy began to decline. But Steely Dan adduced another reason: (ab)normal psychology. The counterculture was an extension of orthodox liberalism insofar as it liked to believe that usually the causes of people’s frustration were external: the environment (in the broader, not merely ecological, sense), the government, an uptight morality, whatever. One of its greatest shortcomings, which Steely Dan rectified to the point of redundancy, was its failure to recognize the unhappiness, if not the evil, that lurks within the hearts of men and women.

What little liberty Steely Dan’s music enjoys is generally sandwiched into its guitar and saxophone solos, which are usually performed, ironically by hired guns — session players. And their lack of faith in freedom has probably encouraged Becker and Fagen to cleave closely, despite their fondness for jazz, to conventional rock structures. The constraints of their songs; formats have been the musical equivalents of their characters’ confinement. Then, too, they distrust improvisation: whereas the ’60s applauded Wordsworth’s “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” and enshrined the indulgent guitar solo, Becker and Fagen, probably convinced that any powerful feelings were vile, scorned romanticism and imposed on their music the strictest controls. Doubtless they were delighted as Steely Dan the group dwindled to just the two of them — as ‘Skunk’ Baxter and Michael McDonald defected to the Doobie Brothers, there was no question who was issuing the orders, and who was following them.

But Becker and Fagen’s fetish for control makes their relation to the jazz that flavors their music equivocal, to say the least. For jazz has almost always depended on, indeed celebrated, spontaneity and improvisation. Steely Dan’s allusions to jazz have sometimes seemed little more than a means of expressing Becker and Fagen’s condescension to rock, of showing off their hip superiority to the medium of the masses. Their best work, however, has given each its due by wittily juxtaposing them: quoting Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father” and a snatch of the Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women” in “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” for instance, or, on “My Old School,” their greatest recorded performance, setting a lurching, almost epileptic, guitar solo against a backdrop of bemused saxophones.

The perplexity of “Deacon Blues” seems to acknowledge, wittingly or otherwise, Steely Dan’s estrangement from genuine jazz. And Aja, their most jazz-like album to date, fails because it cannot overcome, try though it might, a distance it mostly pretends not to recognize. There’s no tension here between warring opposites, for instead of juxtaposing rock and jazz, Becker and Fagen have attempted to homogenize them. Sure, Wayne Shorter plays one solo, but this doesn’t mean diddly-shit when the horns have been “arranged and conducted” by a schlock-meister like Tom Scott and the rhythm charts “prepared” by Larry Carlton, Dean Parks and Michael Omartian. Once distinguished by the quality of their sidemen, Steely Dan are now using the same drones everyone else in LA employs. Aja doesn’t combine the best of both worlds; it reduces rock and jazz to supper-club pablum. Much of this album could have been recorded by Chicago. Becker and Fagen don’t seem to have noticed that “fusion” music has become commonplace — or that a significant segment of the pop audience they have patronized since 1972 has grown considerably more sophisticated than they are (judging from Aja) in its appreciation of jazz. Hermetically sealed in the recording studio, Becker and Fagen have lost touch.

The problem is this: Steely Dan’s initial premises have outlived their usefulness. Becker and Fagen never stood for anything so much as they stood against the ’60, but even Joni Mitchell, for instance, has spent the better part of her career insisting that “free love” is a contradiction in terms. Steely Dan must realize that the decade against which they have reacted so bitterly no longer needs to be debunked. (Pop music today suffers from too much technical perfection and too little sloppy feeling, which is one reason punk rock is so crucial.) The uncharacteristically benign lyrics of Aja are concerned with home and where one belongs because the turf Becker and Fagen staked out has been swept out from under their feet. “This is the day/Of the expanding man,” “Deacon Blues” begins, and Becker and Fagen must expand or else decline into being “nattering nabobs of negativism.” Indeed, the negative impulse behind so much of their music (and lyrics) had begun to yield diminishing returns by 1975 when Katy Lied appeared. The formal perfection of that album did not gloss over its spiritual aridity. and instead of intriguing, the cryptic lyrics to many of the songs suggested that they were about nothing at all — certainly nothing that mattered.

Aja is an attempt to escape Steely Dan’s cul de sac, but bland fusion is another blind alley. At the end of the opening cut, a female chorus intones, rather listessly, “So outrageous.” Yet there’s nothing remotely outrageous about Aja. And just as Becker and Fagen seem, what with their new manager (Irving Azoff) and impending label change (to Warner Brothers), to be on the brink of breaking big, they have become, if not irrelevant, drastically less important.

Letters

Dear Pete and the two other fellas,

I want to thank you for Metal Leg. I’ve been a fan of the Dan since I picked up a copy of Can’t Buy A Thrill at a WooIworth’s Dept. store back in the early seventies. I took it home, Iistened to it all the way through, and I have been hooked ever since. Metal Leg is providing me with the info on Fagen and Becker I have so Iong sought after.

My only complaint is that my new issue of Metal Leg is missing pages 29 and 30. (The Steve Khan Interview). I sure would like to know what he has to say on those two pages. Everything else with MetaI Leg has been great.

I am including this positive review of Donald Fagen’s great solo LP The Nightfly. I clipped this out of a small music tabloid that my brother gave to me a few years back. Maybe you would like to use it in a future edition of Metal Leg. Once again thanks and I look forward to the next issue of Metal Leg and Fagen’s once-a-decade solo LP.

–Kenny Grucholski, Corsicana, Texas

P.S. I’ve just realized that my new issue is also missing pages 7 and 8. I would really appreciate a full or a new intact copy. I would be more than happy to pay for it. Let me know. Thanks.

Sorry about that. Apparently there was a technical malfunction in ‘Metal Leg’s” computerized bindery in Provo, Utah which only affected your issue. After investigating this matter further, we found out the assistant engineer who erased “The Second Arrangement” from Gaucho was responsible for this problem too. Boy, we tried to give this guy a second chance, but he just can’t get anything right. –Bill

Dear Steely Dan Fan Club:

Hello. My name is Tyrone Parker and I’m a big fan of Steely Dan, Donald Fagen and Peter Fogel and Walter Becker. Some of my favorite songs are: “Deacon Blues,” “Home At Last,” “Josie,” “Black Cow,” “Royal Scam” and a few others. I wanted to know if I could start my own Steely Dan Fan Club. Is there a way? How can I get other people to join? And is there any way I could correspond and trade with other members? Steely Dan is a great group and I hope you guys get back together and tour. Please write back.

–Tyrone Parker, Berlin, New Jersey

I really want to tour, but Donald and Walter don’t want to. –Pete

No comments yet.