Originally published on Oct. 6, 2016

By Paul Grimstad

Paris Review

The cover of Steely Dan’s 1975 LP Katy Lied shows an out-of-focus praying mantis floating amid bulbous plants. I used to stare at it as a kid, listening to the record in my dad’s leather reading chair and wondering who this “Steely” was. He sounded sort of like Bob Dylan, if Bob had just been defrosted out of a block of carbonite. (I was intensely devoted to The Empire Strikes Back, so carbonite was almost always on my mind.) Other Steely Dan records like Countdown to Ecstasy, Pretzel Logic, The Royal Scam and Aja opened onto a strange and ominous world: double helixes in the sky, Haitian divorcées, the rise and fall of an LSD chef named Charlemagne, someone who drinks Scotch and then “dies behind the wheel.” The photo on the inside gatefold of the Greatest Hits showed two nasty-looking guys standing in what appeared to be a hotel dining room.

A few years later I found out “Steely Dan” was actually Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, and that their name was lifted from a William S. Burroughs novel (it’s a dildo), a discovery made while ditching seventh-grade social studies to read back issues of Rolling Stone in the public library. (I also learned that that the insect on the cover of Katy Lied was a katydid, not a praying mantis.) As an only child growing up in an unincorporated townlet in Wisconsin, there were many nights when it was just me in the chair and the Dan on the turntable and a few owls hooting in the woods. The sound of Dan music became as natural and enveloping to me to as the countryside itself. It led me to champion the songs of Becker and Fagen among the self-styled punks I later started hanging out with, provoking j’accuse-like denunciations: I was the enemy within, the guy who liked easy listening. I found disses among learned rock pedants in the magazines, too, which I began to catalog: Steely Dan was “hippie Muzak” and “Valium jazz”; their music “sounded like it was recorded in a hospital ward” and was “exemplarily well-crafted schlock”; they were a “brain without a body.” How could these people say such things about songs that were so deviant and bizarre and yet so warm and often staggeringly musical? The fact that the Dan had hits—really huge hits, actually, like “Do It Again,” and “Reelin’ in the Years,” and “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” and “Peg”—only made the whiff of some lurid, freaky luxury in the music seem more pronounced. You could be lyrically weird and musically oblique and still have lots of people like it. A mystery lurked at the center of it all. And the uncut essence of that mystery—the distillation of Dan music, the point beyond which the aesthetic cannot be pushed any further—is their airless, lacquered Masterwerk, Gaucho. Alternately held up as the apex of bloodless studio cerebration and fiercely defended among elite musos as multitrack record making at its finest, the sound of Gaucho is unmistakable. It shows up as recently as Usher’s just released Hard II Love record, the second track of which, “Missin U,” is built entirely around a four-bar sample taken from the last song on Gaucho, “Third World Man.”

A few years later I found out “Steely Dan” was actually Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, and that their name was lifted from a William S. Burroughs novel (it’s a dildo), a discovery made while ditching seventh-grade social studies to read back issues of Rolling Stone in the public library. (I also learned that that the insect on the cover of Katy Lied was a katydid, not a praying mantis.) As an only child growing up in an unincorporated townlet in Wisconsin, there were many nights when it was just me in the chair and the Dan on the turntable and a few owls hooting in the woods. The sound of Dan music became as natural and enveloping to me to as the countryside itself. It led me to champion the songs of Becker and Fagen among the self-styled punks I later started hanging out with, provoking j’accuse-like denunciations: I was the enemy within, the guy who liked easy listening. I found disses among learned rock pedants in the magazines, too, which I began to catalog: Steely Dan was “hippie Muzak” and “Valium jazz”; their music “sounded like it was recorded in a hospital ward” and was “exemplarily well-crafted schlock”; they were a “brain without a body.” How could these people say such things about songs that were so deviant and bizarre and yet so warm and often staggeringly musical? The fact that the Dan had hits—really huge hits, actually, like “Do It Again,” and “Reelin’ in the Years,” and “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” and “Peg”—only made the whiff of some lurid, freaky luxury in the music seem more pronounced. You could be lyrically weird and musically oblique and still have lots of people like it. A mystery lurked at the center of it all. And the uncut essence of that mystery—the distillation of Dan music, the point beyond which the aesthetic cannot be pushed any further—is their airless, lacquered Masterwerk, Gaucho. Alternately held up as the apex of bloodless studio cerebration and fiercely defended among elite musos as multitrack record making at its finest, the sound of Gaucho is unmistakable. It shows up as recently as Usher’s just released Hard II Love record, the second track of which, “Missin U,” is built entirely around a four-bar sample taken from the last song on Gaucho, “Third World Man.”

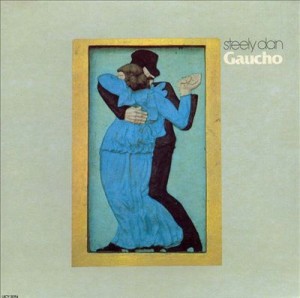

Gaucho took two years to record, is only thirty-seven minutes long, and was the most expensive record ever made when it came out in 1980. The cover art shows a mustachioed man in a black hat doing a tango with a woman whose back is to us, the two of them frozen mid-caress in a yellow frame against a backdrop of speckled blue. The pair are cast in some kind of stucco, giving a tableau-like relief to the image that prepares the ear for the sculpted music within. Drop the needle on the opening bars: three tuned toms slink down to a sumptuously recorded Fender Rhodes electric piano breathing out the first eerie licks of “Babylon Sisters.” There are chords on Gaucho so cold and queasy they make you feel seasick. Reeds, guitars, pianos, horns, synths and human voices form mixtures achievable only in the controlled laboratory of the studio. (Like the Beatles, the Dan had stopped touring to focus exclusively on recording.)

As for the words, here is the second verse of the “Glamour Profession,” the last song on side A:

All aboard

the Carib Cannibal

Off to Barbados

Just for the ride

Jack with his radar

Stalking the dread moray eel

At the wheel

With his Eurasian bride

This is what I mean about lurid luxury: a high-tech yacht equipped with radar for stalking eels. Gaucho is packed with these sorts of perverse details, all with the glazed clarity of an opium trance. Take the title track’s “Custerdome,” which I imagine as a kind of dystopic Civil War memorial/penthouse, the residence of a gay couple whose domestic serenity is upset by a man in a “spangled leather poncho.” The jaded LA scenester in “Babylon Sisters” “jogs with show-folk on the sand” and “drinks kirschwasser from a shell”; on “Time Out of Mind” the narrator “chases the dragon” leading him to junk visions of a “mystical sphere straight from Lhasa, where people are rolling in the snow.” There are also “celluloid bikers,” “Szechuan dumplings” and a detective who wears a hearing aid. Nothing could be further from the tepid clichés of the era’s reigning soft rock.

3.During the recording sessions for Gaucho, audio engineer, computer wizard, and Dan right-hand man Roger Nichols heeded Fagen’s wishes for superhuman perfection in drum performance and custom built a percussion sequencer he named Wendel. Designing and making dedicated hardware to meet the demands of a musician or composer is the sort of thing you might find going on at Pierre Boulez’s acoustic research facility under the Pompidou Centre, but rarely does this happen in the pop world. Yes, Michael Jackson had MIDI percussion triggers sewn into his pants and shirtsleeves so he could build drum patterns while he danced (genius); and yes, Prince actually invented a drum-machine sound, that wonderful clooshk you hear all over 1999 and Purple Rain and Around the World in a Day, which he discovered while experimenting with the tuning parameters on a Linn drum machine; but Wendel was built from scratch. It allowed for superfine inflections—there were sixteen different hi-hat samples instead of the single pulse of white noise typical of the drum boxes of the time—thus avoiding the ear fatigue that results from hearing an identical pattern looped over and over. “Wendel can play exactly what a drummer plays,” Nichols evangelized. And that was important to the Dan, who were known for ruthlessly plowing through ten or twelve drummers at a crack in search of the perfect take (more than forty musicians played on the recording sessions for Gaucho and only seventeen made it onto the record). Wendel was insanely expensive—one crash cymbal cost twelve thousand dollars worth of RAM—and getting the machine to “play” anything was a laborious, coding-intensive process undertaken in the 8085 assembly language, a now obsolete protocol for translating symbolic code into object code. Fagen remembered Nichols typing for twenty minutes and then pressing return for only a single snare hit to come out. It’s crude by today’s standards, but in the spring of 1979 it was, well, the radar equipped eel-stalking yacht of programmable percussion. WENDEL was awarded a platinum record after Gaucho sold a million copies.

4.A few years ago I went to see the Dan play through all of Gaucho at the Beacon Theatre in Manhattan (they started touring again some time in the midnineties). I found a single seat online, right in the middle of the first row of the balcony. We happened at the time to need a new toilet seat in our apartment and my wife, who was staying home to care for our infant son, said, If you’re going out to the Beacon tonight can you get a new toilet seat while you’re at it? I figured this would need to happen before the show, which would start at about nine. So I left early and found one meeting my wife’s specifications at a place just up the block from the theater and then headed over. I’d timed it perfectly: the opening band had just finished and people were getting amped to see the Dan. I did that side-step move you do at a baseball game or a movie theater to reach the middle of a row—actually pretty perilous since I was holding a toilet seat over my head and to my right was a sheer drop off the balcony. I smelled weed and got scared because I thought the contact high would cause me to lose my balance and fall over the edge. When I got to my seat there was almost no room to move because I was squeezed between two Upper West Side Danheads with wispy gray ponytails (one of whom was the source of the weed) so I clutched the toilet seat to my chest and watched as a scarily well-rehearsed nine-piece band played through Gaucho from start to finish. Hearing a couple thousand people collectively singing lines like “bodacious cowboys such as your friend will never be welcome here / high in the Custerdome” and (of course) “the Cuervo Gold, the fine Columbian / make tonight a wonderful thing” was fun, even moving. But I also resented the experience because I wanted Gaucho all to myself, and finally cursed my decision to go to the concert when it would have been better to stay home and listen to the twenty-four-bit remastered version on my Bose noise-canceling headphones. Gaucho burned brighter as a recording, I decided, and I craved the guaranteed exactitude of repeated listens heard again and again, always the same way. The toilet seat, still clutched to my chest on the subway ride home, seemed a fitting (or at least conveniently available) emblem for the way the resentment partially eclipsed the excitement of hearing Gaucho played live.

5.Just about the time a compact disc of Gaucho arrived at the house in Wisconsin (my audiophile father had resolved to replace all of his LPs with copies in the new CD format) I was in the middle of my first slack-jawed read through a mass-market paperback of William Gibson’s Neuromancer. Gleaming silver wafers with laser-encoded music on them seemed to leap right out of Gibson’s technodelic near-future, and what I’m tempted to treat as the mere historical accident of the fully digital Gaucho appearing in tandem with my belated read through the novel has since been dispelled for two reasons: (1) Donald Fagen’s second solo record, Kamakiriad (1993), is a cyberpunk concept album about a hydroponic car with a bionic R & B sound even more frigid and airtight than Gaucho, and (2) Gibson himself has since written a fan essay (“Any ’Mount of World,” 2000) in which he notes his affection for the “paraliterary” songs of Becker and Fagen, referring to the imaginary third entity that results from their collaboration—“Steely Dan”—as appearing in “toe cleavage ostrich loafers flaking red Maui clay on the studio broadloom.”

6.Gibson’s great line neatly captures how far the Dan’s sensibility was from the rest of the lyrics found in standard FM gruel. Fagen and Becker actually allude to the agon with their peers on “Everything You Did” (The Royal Scam, 1976), when a dreary domestic dispute leads someone in the song to say “turn up the Eagles the neighbors are listening.” Less than a year later Don Henley wrote his epic “Hotel California” (which I also listened to and parsed for secret meanings in the leather chair) at the denouement of which the staff of the eponymous hotel try to “stab it with their steely knives but they just can’t kill the beast.” “It” was the hangover of sixties free love idealism and the subsequent trappings of seventies rock stardom: drug and alcohol dependency and various other hazardous enticements from which you may “check out any time you like” but “can never leave.” Some have heard in Henley’s weird adjective “steely” a rejoinder to the Dan. An online video series called Yacht Rock goes so far as to dramatize the backstory of the feud as a playground scene in which adenoidal Becker and Fagen are held in a double headlock by Henley and his fellow Eagle Glenn Frey—jock bullies beating up the eggheads.

7.I’ve since found myself inhabiting a world that seems more and more to have been extracted from some Gaucho–inspired mise-en-scene. My mom (not herself especially fond of the Dan) recently purchased an Amazon Echo, the cylindrical AI that answers questions put to it in real time and which responds to the name “Alexa.” Alexa, what is Steely Dan? I asked on a recent visit to Wisconsin. “Steely Dan is a Grammy Award-winning American jazz-rock band featuring core members Donald Fagen and Walter Becker,” says Alexa. Wow, okay, not bad. Alexa, what is Gaucho? “Gaucho Sport Club is a Soccer Club in Passo Fundo, Brazil.” Nothing about South American cowboys? Alexa, what is Gaucho the Steely Dan album? “Sorry, I can’t find the answer to the question I heard.” Alexa, what is Katy Lied. Alexa: “Hmmm, I can’t find the answer to the question I heard.” Alexa, what is a katydid? My mom: “Paul, leave Alexa alone.” Leave Alexa Alone. It could be the title of a Steely Dan album.

Thanks for your writing. I read this as I was listening to Gaucho and realizing that so much of that collection (album) is so very familiar to me over years of loving Steely Dan’s music. My commitment to these guys was solidified when I heard Aja for the first time. I was working retail in Bellevue Washington and had a really good stereo system; a Sony Superscope tuner-amp, Supersonic “air-suspension” speakers, a Kenwood magnetic turntable with a Shure pickup. I expected to hear songs like My Old School and Bodhisattva and wasn’t prepared for the depth ans sophistication of Aja, the title track. It was a dark winter night above Lake Washington on the hill known as Rose Hill. Being an avid guitar strummer, I could not decipher their sophisticated chords individually, they were not typical structures like 1, 3, 5, 7, 8. They were augmented, diminished, adding 9ths and 11ths, and somehow perfectly connected in series and transitions. There were multiple levels and allegories throughout the masterpiece. Anyway, wanted to share. Thanks again!