By Jon Pareles

The New York Times

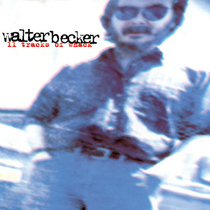

Fifteen years later, we find out who put the edge into Steely Dan. It was Walter Becker, who played bass and guitar and left the lead vocals to his songwriting partner, Donald Fagen. On his first solo album, 11 Tracks of Whack, Becker brings back everything fans cherished about Steely Dan: the desperate characters and elliptical narratives, the jazz harmonies and the ingeniously warped structures. And it turns out he has exactly the right voice for his own words: a groan that’s jaded, long-suffering, cranky and shrewd. The first words Becker sings are “In case you’re wondering, it’s alive and well.”

Becker is as much an oddball now as Steely Dan was during its million-selling reign in the 1970’s. On seven remarkable albums from 1972 to 1979, Steely Dan perfected stealth pop: songs in which calm tempos and suave production cloaked unlikely musical twists and lyrics about topics like stock-market crashes, Puerto Rican immigration or the golden age of be-bop. Only Paul Simon, Randy Newman and the best Brazilian songwriters showed the same musical sophistication, while Steely Dan had a terse cynicism all its own: a fascination with sleaze and duplicity that was one part hipster slumming, two parts film noir. The songs glided onto pop radio stations, and soon the musical surfaces of Steely Dan songs — the Ellingtonian chords, the urbane swagger — were imitated by hack songwriters and easy-listening pop-jazz groups. But few wanted to follow up on Steely Dan’s lyrics or its sneakier musical ploys. The imitators merely recreated the dapper wardrobe, minus the switchblade in the inside pocket. Fagen has made two albums since Steely Dan dissolved in 1980: The Nightfly (1982), a fondly twisted reminiscence of the early 1960’s, and Kamakiriad (1993), a loose travelogue. Becker produced albums, including Kamakiriad, before Steely Dan reunited for summer tours in 1993 and 1994; Fagen and Becker produced 11 Tracks of Whack (Giant 9 24579; CD and cassette) together.

Becker is as much an oddball now as Steely Dan was during its million-selling reign in the 1970’s. On seven remarkable albums from 1972 to 1979, Steely Dan perfected stealth pop: songs in which calm tempos and suave production cloaked unlikely musical twists and lyrics about topics like stock-market crashes, Puerto Rican immigration or the golden age of be-bop. Only Paul Simon, Randy Newman and the best Brazilian songwriters showed the same musical sophistication, while Steely Dan had a terse cynicism all its own: a fascination with sleaze and duplicity that was one part hipster slumming, two parts film noir. The songs glided onto pop radio stations, and soon the musical surfaces of Steely Dan songs — the Ellingtonian chords, the urbane swagger — were imitated by hack songwriters and easy-listening pop-jazz groups. But few wanted to follow up on Steely Dan’s lyrics or its sneakier musical ploys. The imitators merely recreated the dapper wardrobe, minus the switchblade in the inside pocket. Fagen has made two albums since Steely Dan dissolved in 1980: The Nightfly (1982), a fondly twisted reminiscence of the early 1960’s, and Kamakiriad (1993), a loose travelogue. Becker produced albums, including Kamakiriad, before Steely Dan reunited for summer tours in 1993 and 1994; Fagen and Becker produced 11 Tracks of Whack (Giant 9 24579; CD and cassette) together.

Steely Dan was precociously middle-aged. When its leaders were in their 20’s, their lyrics scoffed at youthful passion, and their music had little use for rock’s excesses, preferring the swing and tricky harmonies of be-bop and hard-bop. Becker, now in his 40’s, is staring at actual middle age, and 11 Tracks of Whack, like Paul Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years, applies singular musical ingenuity to visions of shrinking horizons and squandered opportunities. Steely Dan’s snide intelligence has been fused with a sense of mortality.

Becker sings about junkies and cheating lovers, a space alien and a suicidal couch potato, old girlfriends and a spoiled son. Where Steely Dan usually kept a guarded distance from its characters, Becker shows some empathy. In “Junkie Girl,” the narrator watches the hooker he loves die of an overdose; in “This Moody Bastard,” a depressed loner obsesses over his long-gone college sweetheart.

Becker is unsparing in “Cringemaker,” a song about a “college belle” who became “the wife from hell”; after he wonders, with a sardonic female chorus, “Whatever happened to my ha-ha-yeah,” he decides, “I guess we always knew . . . who we would turn into.” In “Hard-Up Case,” a bleak reggae march, the singer realizes his lover has given up on him and found another man, but he takes a parting shot: “Look at what you’re dragging home — another hard-up case.” There’s no melodrama, but no detachment either; Becker’s frazzled, cracking voice is quietly convincing.

Becker’s still smart, still a wise guy, still as cagey as any songwriter in pop. But now, he’s also willing to show some bruises.

With Becker in charge, the songs move toward Steely Dan’s jazzy side. Where Fagen relied on crisp keyboards, Becker features his own guitars, which make the arrangements slippery: notes hover and loop, buzz and tickle, as their sliding pitches reinforce the disorientation in the lyrics.

Naturally, Becker carries on Steely Dan’s musical gamesmanship. Songs start in one key and end in another (“Cringemaker”), bring in new material behind solos (“Book of Liars”) and shift harmony from introduction to first verse (“My Waterloo”). In “Girlfriend,” as the singer watches reruns, the song slouches down through chromatic harmonies; he wonders “Where does a guy like me fit in?” and is answered by a blurting bass-clarinet solo. “Lucky Henry,” about a hobo’s persistent reincarnation, meshes a singsong melody with a double-time jazz vamp; “Surf and/or Die,” about a hang-glider crash, floats glassy chords over an urgent riff.

Yet “11 Tracks of Whack” doesn’t hide behind its own craftiness. “I wear my heart on my sleeve/ A sight you surely must have spied by now,” Becker sings in “My Waterloo,” and for all his self-consciousness, he means what he says. He’s still smart, still a wise guy, still as cagey as any songwriter in pop. But now, he’s also willing to show some bruises. He’s older now; he doesn’t have to worry about being cool.

No comments yet.