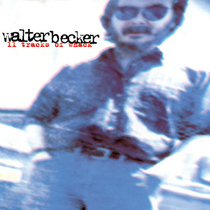

Steely Dan’s resident reticent artist sings his own songs on a new solo album, 11 Tracks of Whack.’ He performs tonight at the Blockbuster Pavilion in Devore.

By Chris Willman

Los Angeles Times

After more than two decades in the public eye, formerly close-mouthed Steely Dan co-founder Walter Becker put himself into the public ear in a direct way for the first time last summer on the duo’s reunion tour by singing a few new numbers of his own. Becoming a lead vocalist this late in the game, and in front of tens of thousands to boot, bespeaks a certain confidence, one would assume.

“I think it’s not so much confidence as just sheer arrogance,” corrects Becker, 44, perhaps not speaking entirely with tongue in cheek. He’ll do it again as this year’s Steely Dan tour visits the Blockbuster Pavilion in Devore tonight and Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre on Friday and Saturday.

“I think it’s not so much confidence as just sheer arrogance,” corrects Becker, 44, perhaps not speaking entirely with tongue in cheek. He’ll do it again as this year’s Steely Dan tour visits the Blockbuster Pavilion in Devore tonight and Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre on Friday and Saturday.

It’s that very attitude of Becker that led to his solo album 11 Tracks of Whack. The long-in-the-making project — due in stores Sept. 27 — was co-produced by the other half of Dan, Donald Fagen, returning the favor that Becker provided in producing Fagen’s ’93 solo album Kamakiriad.

Not that Becker is plagued by delusions about the average concert-goer’s interest in his vocal chops.

“When we originally started last summer, I was doing four songs, and it was ridiculous,” he says, recalling the audience’s anxiety as each new solo number crowded a favorite oldie out of the set. “We had it down to two numbers by about the third show,” Becker admits, chuckling.

Fagen is more explicit about the mettle required of his cohort. “I think it was difficult for him to go out and sing his tunes for the first time. It’s pretty courageous that he’s doing it,” says Fagen, in a separate interview.

“Not that he isn’t a great singer — I think he is in his way, and he’s got a really distinctive voice… But I’m singing all this familiar stuff in my familiar voice, and then for him to get out there and do unfamiliar material with a voice no one’s ever heard… Last year, if people heard something unfamiliar, they’d take that opportunity to go get some steamed clams. And that was their loss.

“This year we’re not seeing that. On one hand, because the album’s release is imminent, I think people are more interested in it. And also Walter does have more confidence this year in his singing, so maybe it’s a little more commanding.”

Fagen finds it “ironic” that he became the singer in the partnership. When the two met at Bard College in Upstate New York in the late ’60s, Becker had been singing and playing harmonica in front of blues bands since high school, while Fagen wasn’t yet crooning at all except to demonstrate his songwriting.

After the duo unofficially split after Gaucho in 1980, Becker concentrated on producing rather than writing. As a corrective to Steely Dan’s legendary perfectionism, this control-room stint was useful, Becker maintains, although hardly all-satisfying.

“The amount of money I made producing records was insignificant compared to what I was making from the (Steely Dan) royalties. But there probably was some sort of Protestant work ethic involved, especially after my son was born. You have a kid and it’s like, ‘He’s gotta go to college! Gotta have some clothes!’

“But mostly it was that I missed it and wanted to get back involved but didn’t want to become involved on the obsessional level that I had been… So producing was good in that way: You could go and do it and not fret over it, and it was kind of your job to be a little detached from it and help the artist by providing that point of view that was not so inside of the thing, and then come home and forget about it… But more and more I got the feeling … of ‘(Expletive), I wouldn’t do it this way.’ I had that thought enough times that it became a do-it-or-hold-your-peace kind of thing.”

The resulting 11 Tracks bears far less resemblance to a Steely Dan album than Fagen’s two solo efforts have. Becker has no problem admitting that his tunes are less “harmonically sophisticated” than Fagen’s. For his part, Fagen — whose writing is keyboard-derived — says, “It’s obvious a lot of Walter’s things are more the type of things a guitar player would write, more derived from folk music and folk-rock, although he also had a jazz background, as a listener, like I did… And with chords, oddly enough, harmonically, he’ll sometimes do something much weirder than I would do offhand.”

Becker’s and Fagen’s lyrical sensibilities are certainly in sync: The album, while surprisingly sweet in spots, like Fagen’s, also features titles — “Cringemaker,” “My Waterloo,” “Junkie Girl” and “This Moody Bastard” — that suggest an ongoing distrust and hearken back to the days Steely Dan was accused of misogyny at worst and misanthropy at best.

Does this often dark outlook square with Becker’s recent life story, which has him surviving drugs and Steely Dan, going through a literal and figurative detox, marrying, settling down and child-rearing in Maui and living happily ever after?

“As a kind of publicity shorthand, that was pretty much the case, that scenario. I’m not as depressed as I was at the time, in the ’70s and early ’80s. But those are still the interesting things to write about, let’s face it. That hasn’t changed that much.

“Obviously I was drawn toward this mood or this perception of the world that I had, and I experienced it and wallowed in it until I was tired of it. And I had so thoroughly immersed myself in it that I was able to move away from it without ever feeling like, ‘Wow, geez, I never quite got to do this’ or ‘If only I could’ve done that.’ It’s something you go through.

“If you think about the things you went through in adolescence, how silly or distant you feel from them now, that’s how I feel about that. I’m not saying that I have the most chipper disposition in the world or that that seems utterly alien to me, but, on a general basis, I have a very different outlook than I did.”

No comments yet.