Editor’s Note: From 1987 through 1994, diehard Steely Dan fans turned to a small fanzine called Metal Leg for information about Donald Fagen and Walter Becker. Published first by England’s Brian Sweet (who went on to write the unofficial band biography Steely Dan: Reelin’ In The Years) and later by New Yorkers Pete Fogel and Bill Pascador, Metal Leg set high standards by providing solid information without resorting to paparazzi-style tactics.

Articles

Editor’s note

I’ve Got The News

Georg Wadenius Interview

Reelin’ In The Years Book Excerpts

The Dead Band Society

“Woodstock Warren” Bernhardt

Classic Tracks

Letters

Editor’s Note

Here we go again. Or should we say, here I go again. I thought I’d have to wait another 19 years to see Steely Dan play live, but I guess things have changed. Maybe Donald & Walter had as good a time as I had last year. I’m looking forward to going to cities that they didn’t play last year, especially the Portland and Seattle area shows where we have a tremendous number of subscribers. You all know what I look like by now, so come on by and say “Hi.” But please don’t ask me what “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” means.

We just obtained a copy of Walter’s new record which is due out on September 27th. We think you’re really going to dig it. We sure did. Just think, after an 11-year drought, we get a Donald solo album and a Walter solo album, both within a 16-month period. Maybe the idea of a new Steely Dan album doesn’t seem as far-fetched as it did a couple of years ago.

In closing, we’d like to thank everyone who re-subscribed with the last issue. It was the most resubs we’ve seen since we took over the magazine.

–Pete

I Got The News

Whack (n.) 1. a blow, intermediate in intensity between a whallop and a smack. 2. a first stab or crude attempt i.e. “Let your little brother have a whack at the circular saw!” (v.) to deliver a whack, ambush, or attempt to wipe out, a person. ( adj.) jive or inauthentic or otherwise bogus, although somewhat diverting in a trashy and contingent sort of way.

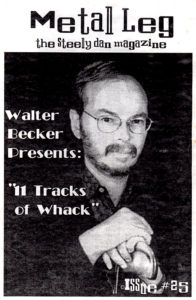

11 Tracks Of Whack is the title of Walter Becker’s debut solo album which will be released on Giant Records on September 27th, 1994. The album is co-produced by Donald Fagen and was completed in July at Walter’s studio in Maui.

Although Walter’s El Lay-based publicist refused to supply Metal Leg with an advance copy of the album and press release (“only major publications get advance copies”), we refused to accept this snub of our readers. With the assistance of some FOML’s (Friends Of Metal Leg) in the Clinton administration, Metal Leg’s editor and publisher made a clandestine journey to Los Angeles to obtain a copy of the promo tape and press release. And in a daring covert operation staged two nights prior to press time, your editor and

publisher made a midnight parachute jump into the rear parking lot of the publicist’s Santa Monica office, performed a near perfect dumpster dive, and located a discarded tape and press release after only two minutes of sifting through empty sushi take-out cartons and Evian water bottles. Mission accomplished!

And the reward was worth the risk. Walter’s album is awesome, original and quite funny. The 12-song titles on 11 Tracks of Whack are “Down In the Bottom,” “Junkie Girl,” “Surf and/or Die,” “Book Of Liars,” “Lucky Henry,” “Hard Up Case,” “Cringemaker,” “Girlfriend,” “My Waterloo,” “This Moody Bastard,” “Hat Too Flat,” and “Little Kawai.” Although we haven’t had the time to let the album sink in yet, our favorite lyrics so far are in the chorus to “Junkie Girl”:

No foolin, it’s a fucked-up world

So be cool, my little junkie girl

The press release we retrieved in our California expedition contained the definition of the word “whack” and also the following biography of Walter:

“Born in New York City in 1950, Mr. Becker makes his debut as a music lover while huddled in the back seat of his father’s cream and flesh colored Ford Fairlane. As it hurtles down the Henry Hudson Parkway, he watches the advertising billboards slide by, and is hypnotized by the rhythmic swooshing of the wipers and the mottled half-light shining through the rain-swept windshield. He begins to enjoy the bland but tuneful renderings playing on the dashboard radio. Later, he takes to staying up late for the Steve Allen Show, singing along with its famous musical theme, ”Gravy Waltz.” Steve comes on and he’s playing some sort of weird harmonica with a keyboard — it’s a Melodica. Becker gets one and soon enough he’s playing along most every night. The Melodica was a bust but soon Becker’s interest has moved on from the Steve Allen Show to Miles Davis records, and he’s now aspiring to play the saxophone. He presents his case to his father who reluctantly accompanies him to Manny’s Music Store, where a used tenor is obtained, along with a box of reeds. Lessons are arranged, which proves to be tiresome, and anyway one night Becker hears a Bob Dylan record on the radio. The saxophone is also a bust but Becker has saved enough money by Christmas of the next year to buy a small acoustic guitar. Braving the Long Island Railroad (the subways are on strike) he returns to Manny’s and gets himself a Martin guitar, a harmonica and a harmonica holder. Pretty soon he is strumming along with his favorite records, using the chords he copped from his friend Harold, a guitar owner in his own right. By the time he gets to college he can play all the important blues licks on the electric guitar and is working on the electric bass. Plus, he has written a couple of tunes for his high school blues band. This is when he hooks up with Donald Fagen, and the two begin plugging away in earnest. Then Steely Dan. With two successful singles, namely, “Do It Again” and “Reelin’ In The Years,” their first album, Can’t Buy A Thrill quickly goes gold. The group goes on to record a total of seven commercially successful and critically acclaimed albums, including Pretzel Logic (1974), Aja (1977) and Gaucho (1979) as well as numerous hit singles which are selling briskly and receiving substantial airplay to this day. After which, by 1980 or so, Steely Dan is kaput and Becker is sorely in need of a change of pace. He moves to Hawaii, forswears the use of tobacco, strong drink, etc., etc., and begins a process of physical and spiritual regeneration which, it is hoped, will carry him into his fourth decade and well beyond.

At this time, he meets his wife Elinor and they have a child together, a boy called Kawai, but only months before the child is born Becker relapses — not into drug or drink or smoke but back into The Music Business. Seeking easy work and quick gratification, he casts himself as a record producer, working first with a band called China Crisis, and later with others, including Rickie Lee Jones, Lost Tribe, jazzers John Beasley, Bob Sheppard, Andy Laverne, and others. Finally he co-produces Donald Fagen’s second solo album, Kamakiriad, and as he is doing so he is feverishly scribbling down the demented lyrics for his own solo album, 11 Tracks of Whack.

So why does a 40-year-old veteran of the recording business suddenly decide he wants to make his belated debut as a recording artist/vocalist? “Producing turned out to be a less than satisfying job, in most respects,” Becker recalls. “It’s impossible for the producer to be ultimately responsible for the overall esthetic of the album, because most of the important decisions are made by the artist — as well as the actual performances. So you end up sitting there, thinking that you should have done this or that differently, or not at all, or whatever. Plus, you never quite get to experience the satisfaction of having conceived something from the very beginning, of making something from nothing, which you get from writing … At some point I decided that the artists I was producing were having all the fun, and that the only way to continue was to become the artist myself. Whatever that would mean, in terms of what kind of record I might want to make — I wasn’t quite sure to begin with. But I decided to find out.”

Becker starts off with a series of instrumental pieces, just to get back into the swing of things. “My original concept involved a very stripped down sound, with strong emphasis on melody and bass line, and not too much in the way of chording. The idea was to get a kind of spacious feel, where the harmonies were more defined by melodies and roots than spelled out with static vertical comping type chords.” As he became more proficient with his tools — mainly synths and computer sequencing programs — they became integral aspects of his compositional technique. “My first dilemma was, how do I go about writing by myself, that is, without Donald? In our collaboration, he provided a lot of the harmonic direction and overall tonal framework, and his ability to develop great chord sequences, striking modulations and so on, became an essential ingredient in our writing style. “I decided to use a minimalist approach that would enable me to focus on the overall thrust of the song, rather than bogging down in harmonic complexities and ornaments that were perhaps irrelevant in the musical context of the day.” As far as lyrics went, he was able to continue much in the vein of the Steely Dan songs, but with the added freedom of veering off into areas that might have been too personal or bizarre for even his and Fagen’s eccentric territory. “When you’re collaborating, you often need to persuade your writing partner that an idea is interesting enough or strong enough to work with, and sometimes get to follow your hunches a lot more. I also took advantage of events unfolding in my immediate environs as subject matter for songs in a way that was somewhat different from what we used to do… Generally speaking, I tried to suspend my critical perception of what I was doing, musically and lyrically, until I had completed something, so as to range out a bit in new areas. This experimental approach was helpful in maintaining a flow in my writing.”

When it comes time to begin the recording process, Becker calls on a rhythm section from the band Lost Tribe — that is, Adam Rogers on guitar, Ben Perowski on drums, and Fima Ephron on bass, plus guitarist Dean Parks and keyboardist John Beasley. The band works for a couple of weeks, and three tracks wind up on the finished album. The rest of the tunes, Becker decides to base on his sequenced demos which he feels capture the essence of the tunes. “I had to spend a good deal of time coming up with a vocal approach that I liked. Some tunes were more daunting than others. And in most cases, it seemed that singing over the track with which I had written the tune worked out for the best.” After several months and following the Summer ’93 Steely Dan Tour, Donald Fagen comes out to Hawaii to help Becker finish the record — a process which as it turns out takes many more months. “I was driving myself nuts by the time Donald arrived. Luckily he was able to steer me in the right direction and take on the bulk of the production chores at a point when I was glad to be able to concentrate on other things, singing and so on.” By July of ’94, 11 Tracks of Whack is a done deal — Becker is back in Hawaii, getting ready for another Steely Dan summer tour, during which he will perform a number of tunes from his new album for the first time, with the capable backing of Fagen and the rest of the Steely Dan touring band. Fagen is back in New York working on charts for the band. “Now that the thing is finished, I realize that writing words and music is the most enjoyable and satisfying part of the process, and something I was missing in my life. Now that I’m doing it again, I kind of feel like I have rediscovered some of the excitement I experienced in the beginning of my career, writing with Donald and later making those first few albums.”

Make sure that you send Metal Leg any interviews with Walter and reviews of his album that appear in your local’papers so we can use them in our next issue.

We are· also taking bets on how many of the headlines will utilize variations of the word “whack” e.g. “Walter Becker Gets Whacked,” “Walter Becker Goes Whacky,” “The Whacky World of Walter Becker,” etc.

New York and Philly are out. Miami and Dallas are in, as the Citizen Steely Dan Tour ’94 bits the road on August 19th, 1994 at St. Petersburg, Florida’s Suncoast Dome. The dates, as of press time, are the following:

8/19-St Petersburg; FL-SuncoastDome

8/20-Orlando, FL-Orlando Arena

8/21-Miami, FL-Miami Arena

8/23-Columbia, MD-Merriweather

8/24-Mansfield, MA-Great Woods

8/26-Chicago, IL-Poplar Creek

8/27-Clarkston, Ml-Pine Knob

8/28-Columbus, OH-Polaris

8/30-Raleigh, NC-Walnut Creek

8/31-Atlanta, GA-Lakewood

9/2&3-Dallas, TX-Starplex

9/4-Houston, TX-Woodlands

9/6-Denver, CO-Fiddler’s Green

9/9-Vancouver, BC-Coliseum

9/10&11-George, WA-The Gorge

9/13-San Francisco, CA-Shoreline

9/14-San Bernardino, CA-Blockbuster

9/16& 17-Irvine, CA-Irvine Meadows

9/18-Phoenix-Desert Sky Blockbuster

There are currently no shows planned for New York and Philly and there aren’t any rumors that they may be added. Regardless, you should pay attention to your local radio stations just in case they decide to add some shows like they did last year. If they don’t add New York or Philly, all we can say is that we’re SOL and hope they decide to tour next summer.

For those of you who might look to travel to the tour cities sans tix, you should call some of the TicketBastard (Master) outlets. Some lawn seating is currently available at several shows. If you want better seating, the chances are good that you could get tickets at face value by showing up an hour before showtime and looking for people with extra tickets to unload. (Venues where you have to show your tickets to park are more of a problem, e.g., Great Woods.)

The Steely Dan Orchestra ’94 contains many of the same members as last year:

- Warren Bernhardt – Piano

- Tom Barney – Bass

- Bill Ware – Vibes

- Bob Sheppard – Sax

- Chris Potter – Sax

- Cornelius Bumpus – Sax

- Brenda King, Diane Garisto & Catherine Russell – Backup vocals

New additions are Georg Wadenius on guitar, replacing last year’s Drew Zingg, and Dennis Chambers on drums, who will take the throne left vacant by Peter Erskine. Metal Leg conducted an interview with Wadenius, which appears elsewhere in this issue, so you can get his story there.

Dennis Chambers, the highly-acclaimed funk and fusion drummer recently won Modern Drummer’s readers poll as #1 drummer in both the jazz and funk categories. Dennis has played on numerous albums, most notably with George Clinton and P-Funk and the P-Funk All Stars (Live at the Beverly Theatre, Hey Man, Smell My Finger CDs), Steve Khan (Headline & Crossings), and Charles Blenzig (Say What You Mean). Chamber’s first full-length solo album Getting Even was released in 1992 and is only available in Japan.

Chambers’ playing draws from many influences. He told Modern Drummer magazine, “I grew up in a jazz-fusion club. When I leanrned how to play, it was basically by listening to a lot of jazz, fusion, R&B and soul music. That’s how I learned to play. I had no idea that a lot of guys were sort of specialized, like bebop drummers who were strictly into bebop. I know some people who went through their whole career’ with blinders on. They were in their own little world. The rockers were into rock, the j_azz guys were into jazz and the Latin guys were into Latin. The soul guys had their fingers i_n a few more things other than soul music. But because of the way I grewup listenirig to all kinds of music, I thought that was what it was about.”

Of the set list, there will be a few changes from last year’s program, but don’t expect a completely new show. They will do some Steely songs, some Donald songs and some Walter songs. We’re not going to divulge any of the new songs, but look for two songs from Scam, another one from Thrill, and other surprises.

As he did last year, Pete Fogel will be covering a number of the shows for Metal Leg. He won’t be able to attend all of the shows like last year, but will be able to see the majority of them.

For those of you attending the Denver show, you are invited to a post-concert party featuring the Steely Dan cover band, Kid Charlemagne, at the Herman’s Hideaway club just south of downtown Denver.

Kid Charlemagne, a nine-piece band, which features Metal Leg subscriber Dave Demichelis and Georg Wadenius’ former Blood, Sweat and Tears bandmate Tony Klatka as members, is offering Metal Leg readers and their friends free admission to the party by showing your concert ticket stubs at the door. Metal Leg Editor Pete Fogel will also be signing autographs at the party.

Don’t forget to send Metal Leg any Steely Dan tour interviews, previews and reviews for us to use for our next issue!

Steely Dan live album

Warner Brothers, which had originally said it would release a double CD set in time for Christmas ’94, has just pulled it from their release list and the project is currently in limbo. We understand that this year’s tour will also be recorded, so the project is not dead, it’s just been delayed. We’ll keep you up-to-date on the status of this eagerly anticipated album.

Big Noise, New York

The B-side to the CD single of “Snowbound” from Donald’s Kamakiriad has been getting heavy airplay on New York’s contemporary jazz station CD101.9. Whenever the song plays on the station, the DJ’s always get bombarded with phone calls from listeners wanting to buy the song. For those of you wanting to buy the domestic CD single, the catalog number is Reprise Records 9-18319-2.

If any of you thought that the funky old man pitching Nike shoes on recent TV ads looked familiar, you’re right. It’s William S. Burroughs, the author of Naked Lunch. Maybe the Nike people will approach Becker and Fagen to appear in their next ad campaign. How does “Just Do It Again” sound? We think it could sell sneakers. Look what John Lennon and The Beatles did for them.

Drew Zingg, the tour guitarist with the New York Rock & Soul Revue and the Steely Dan ’93 Orchestra has just finished a short tour stint with David Sanborn. Ex-Metal Leg pinup girl Mindy Jostyn, the backup singer with the New York Rock & Soul Revue, has been winning critical raves for her recent tour work as a backup singer with John (“Jack & Diane”) Cougar Mellencamp.

Kevin Bents, another NYR&SR alum, plays piano on Boz Scaggs’ new album, Some Change and is also playing guitar with his own NYC band “Play.”

In Gary Katz news, his work with the band Repercussions, who were featured on the recent Curtis Mayfieid Tribute album, will finally be released on Warner Brothers in early 1995. Gary has also been working with the New York rock band Helmet as well some other bands we’ll cover in the next issue. If you look real closely on the back of the CD booklet for the acid jazz group, Groove Collective, recently produced by Katz, you can see a snapshot of Donald Fagen with vibe player Bill Ware.

In River Sound news, Aerosmith have been working in the Katz/Fagen-owned studio.

And, in a belated obituary, Manhattan’s Lone Star Roadhouse, the venue that served as the site of the Steely Dan reunion in October 1991, as well as the birth of the New York Rock & Soul Revue and Libby Titus’ New York Nights has gone out of business. The doors closed on January 1, 1994.

Live, from Sweden, It’s … Georg Wadenius

Georg Wadenius, that’s Georg without the “E,” is joining the Steely Dan ’94 Orchestra as their new guitarist. Filling Drew Zingg’s shoes is not an easy task, but Georg, a native of Sweden now living in New Jersey, is up to the challenge. With years of studio and touring experience with such names as Blood, Sweat & Tears, Simon & Garfunkel, and Roberta Flack, Georg’s association with Steely Dan actually started with playing on Donald’s “Century’s End” and Kamakiriad. Although Georg has been mostly been viewed as a rhythm guitarist, he’s ready to step out and show that he’s a helluva soloist. In this interview conducted in late-Spring ’94, Pete Fogel talks to the new Steely Dan guitarist.

Metal Leg- When did you come to New York from Sweden?

Georg Wadenius- The first time was in 1972. I was working with Blood, Sweat and Tears; that lasted for three and a half years.

ML- Was that the band with Al Kooper?

GW- No, Al Kooper was in ’67, I think. The band that I was in had a singer named Gary Fisher from down in Louisiana, otherwise there was a bunch of guys, Bobby Columby, Steve Katz, but there was a lot of changes — Lou Marini came in and so did Tom Malone.

ML- Did you play on any records?

GW- Yeah, I played on some records — one was called New Blood, one was called No Sweat, one was Mirror Image, and one was New City.

ML- Did they let you stretch out on these albums?

GW- A little. It was mostly rhythm. I did play some solos. I played a long solo on “Maiden Voyage.”

ML- When did you work with Grace Slick?

GW- I played on an album of hers, it must have been about 1979-80 and I don’t know what came of it

ML- You also played with the Saturday Night Live Band.

GW- I got the gig through a couple of the guys in Blood, Sweat and Tears. I came back to New York after being back in Sweden for a couple of years. Tom Malone and Lou Marini were doing the Saturday Night Live gig and I had contacts with them. They decided to get another guitar player and I and a few other guys auditioned for the gig and I got it. That was a good gig.

ML- Was Eddie Murphy a cast member at that time?

GW- Yeah. I started the last season with Belushi and Aykroyd and then with Murphy and Piscopo.

ML- You also worked with Roberta Flack, right?

GW- Yeah, I toured with her in 1980. That was something I got through doing Saturday Night Live because her bass player Marcus Miller recommended me for her gig. I only played with her for perhaps a year. Roberta was going to Australia, but we were going to have our second child and it was a month away so I couldn’t go. That was one of my all-time favorite gigs.

ML- Was it mostly rhythm guitar you were playing?

GW- Yeah, with Roberta mostly rhythm.

ML- What about playing with Simon and Garfunkel?

GW- There were some lead things, but it was mostly rhythm.

ML- You told me you have an eight-track recording studio in your house.

GW- Yeah, I write for commercials every now and then.

ML- You’ve also recently been involved in a project with a couple of guys who have worked with Pat Metheny.

GW- Yeah, it’s a band called Elements with Mark Egan, Danny Gottlieb and Cliff Ward. Cliff is currently out now with James Taylor.

ML- Moving to Steely Dan, word has it that Donald and Walter are now into using bass players and guitarists with funny last names. Do you think that’s how you were chosen?

GW- (Laughs) I hope there’s something more to it than that

ML- What was the first project you’ve worked with them on?

GW- The first thing I worked on was the soundtrack to Bright Lights, Big City. That was because of Rob Mounsey, I know him from commercials.

ML- This was time first time you worked with Donald?

GW- Yeah. Rob was the one that brought me in to do that and that’s when I met Donald. It was kind of a bluesy thing that we did, you know.

ML- If you watch the movie, there’s a lot of fills. Did you play any of the music in between the scenes?

GW- l only played on two things and one of them was “Century’s End.”

ML- Did you play that alone or with a rhythm section?

GW- It was with a rhythm section, but it could even have been sequenced.

ML- Just you in the studio with your headphones?

GW- Yeah.

ML- Was the song completed when you played on it?

GW- No, just drums, bass and keyboards.

ML- No vocals?

GW- No.

ML- I think that song started a new sound for Donald.

GW- I’ve always liked Donald and Walter’s stuff. I’ve always loved that guitar work.

ML- When did you first start listening to them?

GW- Probably when I was with Blood, Sweat and Tears. There was some great unique stuff about them. I remember meeting Elliot Randall in 1973 or 1974 and talking to him about it.

ML- Did you see them Iive back in 1974?

GW- No, I never did.

ML- Do you think that your time in Blood, Sweat and Tears has helped you to work with Donald and Walter?

GW- In a sense I think it’s a maturity process when you come into a situation and you’re working for someone else. Some people come in thinking they’re really hot shit and what they do is the right stuff; whereas I really learned in the last 10 years to come in and someone asks you to do a certain thing and it’s okay. You ask them what they mean if you don’t understand and you just communicate. It’s been good for my ego to do that. So when I get to work for somebody like Donald and Walter who are sometimes very specific as to what they want, I don’t have any ego that gets in the way.

ML- You played on “Century’s End” and around that time you gave Walter a record that you had played lead guitar on?

GW- Yeah, we did actually get together and just jam together one day. This was two or three years ago.

ML- When they called you in to do Kamakiriad were you thinking “I’m gonna be doing rhythm again?”

GW- No, I didn’t really have any idea what it was. I assumed it was rhythm. For some reason I have not been doing much lead work in New York at all. On commercials I do tons of lead work, but on record I haven’t.

ML- So now you’re going out on tour with them and playing all these great songs that let the guitar players shine, and yet they really have little concrete evidence of your lead guitar playing. It’s a little weird.

GW- Right, I think so, too. They must have talked to someone or I guess they just trust that I can do it.

ML- Does any song from “Kamakiriad” stick out in your mind as being the hardest lo achieve what Donald and Walter were looking for?

GW- Yeah, I can’t remember exactly what song it was, but it was a couple of songs towards the end. “Teahouse on the Tracks” was one that was kind of hard. What’s the one about the amusement park?

ML- “Springtime.”

GW- “Springtime,” yeah. Basically I doubling what the keyboard is doing. That was a hard part because the voicings were so clustered and it’s not so easy to play on a guitar.

ML- Which one was the easiest?

GW- The first one on the album.

ML- Trans-Island Skyway.” Did you play on every song?

GW- Yeah.

ML- “On The Dunes” is the only one where you were allowed to stretch out a bit.

GW- Yeah, that’s the only one where I have a few fills.

ML- Were you the only musician in the studio?

GW- No other musicians, just Donald and Walter and an engineer, Wayne Yurgelun or Tony Volante. Roger Nichols wasn’t there when I worked with Tony, it was either Roger or one of the other two guys. When we started working up at River Sound, that was with Roger.

ML- Have you been familiarizing yourself with some of the Steely Dan tunes in preparation for the tour?

GW- Yeah, I go through a couple of days and listen to a lot of their stuff.

ML- If Donald and Walter came up to you and said ‘Georg, pick three songs to play live,’ which ones would you pick?

GW- It’s hard. I love The Royal Scam album. I think it’s my favorite of their albums because I love Larry Carlton’s playing. I’m surprised they didn’t do “Kid Charlemagne” because that’s a killer.

ML- I heard they did rehearse it.

GW- I like “Third World Man,” but I like a lot of their stuff. Musically I’m really into tunes that are a little different. I’m not so much into their earlier stuff. I’m much more into The Royal Scam and on. I like a few tunes on Katy Lied, too.

ML- Did you see any of the shows last year?

GW- I saw the one at Madison Square Garden. I think the sound was horrible, but I loved the band. It was just a bad mix. It was all bass drum, I couldn’t hear Tom Barney’s bass playing at all.

ML- What was your impression of Drew?

GW- I thought he was great, very impressive. He has great chops. I don’t have the chops he has.

ML- Drew told us that you gave him a ring and asked him about his rig and stuff.

GW- Yeah, I did, because I wanted to find a guitar that had a Gibson scale, which is a slightly smaller scale than a Fender, but still has a Fender sound. I knew that he had one built. They never quite sound like Fenders, they never have the Fender scale, so I ended up not having it built.

ML- How would you describe the difference between your playing and Drew’s playing?

GW- That would be very hard to tell. We both have different personalities.

ML- Are you gonna consciously do anything different?

GW- They gave me a tape of the shows from last summer. I listened to his playing and he plays a lot of great stuff and I think I have to learn what it is in a way, and then I really have to move myself away from it and not be too affected by it. If we did “Kid Charlemagne,” I’d probably play the solo exactly the way it is because that is almost as important as the tune, I think.

ML- When do you start rehearsals for the tour?

GW- Beginning of August.

ML- Have they given you any hints about what songs you might be doing?

GW- They said there might be five or six different tunes, so that will be interesting to see what that means. No, they didn’t tell me which ones. As soon as they know they’re supposed to let me know. We’re only gonna rehearse for a.week and a half — if that even — and it’s a lot to learn 25-30 tunes.

ML- Have you any idea why they keep changing musicians around?

GW- I don’t know why. Maybe it’s to keep it interesting for themselves.

ML- Have you ever played with Dennis Chambers or Tom Barney before?

GW- Dennis was on the Saturday Night Live band for a couple of years and I’ve done a lot of sessions with him. I know Tom pretty well. And I know Warren Bernhardt, too.

ML- Do you have any funny Donald or Walter stories to share?

GW- Walter’s funny because he’s called me a couple of limes. One of the things I did with Blood, Sweat and Tears was a lot of scat singing and I have talked to Waller about that. So once he was doing an album with Jeremy Steig and he wanted me to play on that and he called me up and the first thing he says is (in a disguised voice) ‘Oooh, are you so and so?’ and I say ‘Sure’ and he’d say ‘Well, I’m a producer here in L.A. and I’m really looking for that characteristic scat singing sound and I remember hearing you on some record a while ago and I wonder if you could come out here and …’ After a while he said ‘Hi, it’s Walter.’ He really bad me going.

Reelin’ In The Years, by Brian Sweet (Exclusive excerpts)

Brian Sweet, the esteemed British founder of Metal Leg, has finally had his unauthorized, tell-all biography of Steely Dan, Reelin’ in the Years published in England. By the courtesy of Mr. Sweet and his publisher Omnibus Press, Metal Leg has been given the following excerpts for your reading pleasure. The book will be available in the U.S. in mid-August.

To give you an idea of the tone of the book, we have reprinted the notes that appear on the back cover of Reelin’.

Reelin’ In The Years is the first ever biography of Steely Dan, the supercool American jazz rock “band” who have sold over 50 million albums during an up and down career lasting over 20 years.

It tells the strange tale of how Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, a couple of cynical New York jazz fans, wormed their way into a record contract and astonished critics with the first Dan album Can’t Buy A Thrill in 1973. Nine albums later, after Aja had topped charts everywhere, they were among the biggestselling acts in the world. Then they quit, only to reform in 1993 more popular than ever.

But Steely Dan were different from the rest of rock’s super-sellers. They rarely gave interviews. After some early bad experiences on the road, they refused to tour. They didn’t have their photographs taken. Few people knew what they looked like. Steely Dan wasn’t even a proper group; it was two musicians and their producer, yet every top notch player in the world lined up to appear on their albums. They were perfectionists. They were enigmatic. They were very rich. Their music was the coolest around.

In Reelin’ In The Years, Brian Sweet, editor and publisher of Metal Leg, the UK-based Steely Dan fanzine, finally draws back the veil of secrecy that has surrounded Walter Becker and Donald Fagen. Here for the first time, is the true story of how they made their music and lived their lives.

‘Reelin’ In The Years follows this mysterious pair through the Steely Dan years, their work apart and beyond, right up to their surprise decision to reform the band. It is one of the most remarkable tales in rock. It is a must for anyone with a Steely Dan record in their collection.

Includes many photographs and a complete discography.

(Editor’s note: Please note how Mr. Sweet is listed as the editor and publisher, and that Metal Leg is supposedly U.K.-based. This is news to Pete and Bill, who, while residing in New York City, have been the editor and publisher of Metal Leg for the past four years.)

Excerpt One: “Meet Jerome Aniton”

On their 1974 U.S. tour Steely Dan had hired a truck driver cum emcee called Jerome Aniton. He was a character quite unlike his employers with an unquenchable thirst for alcohol and a devil-may-care attitude that perversely, Becker and Fagen admired to no end. His fondness for alcohol did wonders for his introductions, and on more than one occasion he crashed the equipment truck. At the prestigious Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, where at that time Steely Dan were the only rock ‘n’ roll group permitted to play, Aniton did thousands of dollars’ worth of damage driving their equipment truck out of the building, smashing a massive hole in one trailer which housed most of Dinky Dawson’s personal possessions. It was raining torrents as Steely Dan’s crew drove on to their next gig in Boston so someone had to crawl up on to the top of the trailer and try to patch the hole over before the gear inside was ruined.

On another occasion Aniton drove from Baltimore to Washington at night without headlights accompanied by two 15-year-old girls in the front seat. He was accident prone and incessantly intoxicated, and ought not to have been allowed to continue with such responsibility, but Becker and Fagen had taken a shine to him and insisted he be retained in some capacity.

So Aniton became the comedian of the party, sending the band into paroxysms of laughter with unconventional behaviour he considered normal. Aniton was given the responsibility of introducing the band on stage and his introductions were exaggerated interpretations of what an emcee might say at black soul revues. Aniton was a truck driver doing his take on a black emcee while under the influence of alcohol and presenting a white band … but it worked a treat. He gave some memorable and hilarious introductions, and even became something of a favourite among fans who relished yet another unexpected quirk of Steely Dan. The first time be introduced them, the band enjoyed it so much they played the opening song better than ever before.

Part of the fun was that Aniton didn’t even understand Steely Dan … he actually thought Donald Fagen’s name was “Stevie Dan.” On one occasion, ever unsteady on his feet, Aniton stumbled into Fagen’s grand piano on stage and said to one of the other players, “I bumped into Stevie’s piano.”

His introductions varied nightly from “Stevie Dan” to “Mr. Stevie Dan and Whatever.” The more Aniton drank, the more hilarious his introductions became so everyone encouraged him to partake as much as possible. Aniton might go on and do a rambling two-minute-plus introduction replete with expletives while the band members laughed aloud behind him, encouraging him with audible asides. At a gig in Cleveland, Aniton’s geography deserted him and he referred to the city as being on the east coast.

Excerpt Two: Meet Denny Dias

Becker and Fagen’s intention had always been to form a band based exclusively around their songs and they were always on the lookout for alternative outlets for their material. In the summer of 1970 they noticed an ad in the ‘Village Voice which read:

“Bass and keyboard player required, must have jazz chops. No assholes need apply.”

The phone number listed belonged to a guitar player called Denny Dias who lived out in Hicksville on Long Island.

Walter Becker called Dias at his home. During their conversation, Dias told Becker that the group wasn’t sure if they really wanted a piano player after all. Becker told Dias that he would bring along his partner anyway. ”When you hear the piano player, you’ll change your mind,” Becker assured him.

Denny Dias was born in Philadelphia in December 1946. His parents moved to Brooklyn when he was still a baby and moved on again to Hicksville when he was eight. His parents were both music fans, invariably tuning into the “Colgate Paimolive Hour” to watch Louis Armstrong and other popular artists of the day. Denny got his first guitar, a $5 model with only three strings, when he was 12, but he wasn’t interested in it and the guitar stood in a corner until one day a cousin started studying guitar and this inspired Dias to start teaching himself to play. Once he had attained a certain level of proficiency, he sought professional tuition and went through several tutors until he found Billy Bauer, the Metronome Poll winner of 1946, who not only taught the guitar but music theory as well, and eventually Dias majored in music at college. He was uncertain as to which course to take and changed to engineering, switched again to math and, when he graduated junior college, attended downstate medical school studying computer science as related to medicine. But by now, music had become his chief interest and he lasted only one term at college before deciding to take a year off from studying academically to “see what happened.” He figured that the opportunity to study would still be there next year and he desperately wanted to try his band as a full-time musician.

Dias played in the Hicksville High School dance band but his first real group was called The Saints — whose theme tune was rather unimaginatively “When The Saints Go Marching In” — and he had been in various groups throughout the years, including one called The Grapevine. By 1969 he was the guitar player in Demian, a band named after a Hermann Hesse novel. Demian’s Italian-bred bass player, Jimmy Signorelli, had quit the group to return to college, which is why Dias placed the ad in the “Village Voice.” Before Signorelli’s departure, Demian had been gigging as a four-piece at nightclubs in and around Long Island, playing Top Forty covers, some older Top Forty songs and material which really interested the band — soul tunes such as James Brown’s”Cold Sweat,” The Four Tops’ “Reach Out, I’ll Be There,” Sam and Dave’s “Hold On, I’m Coming” and, inevitably, a couple of Otis Redding numbers.

Demian’s lead vocalist was an ex-lifeguard and cab driver called Keith Thomas, who had been friends with Dias since their grade school days. “We were bored to shit,” Thomas said of their enforced live chart covers. Dias and Thomas were both writing their own songs but audiences generally wouldn’t allow them to play their own material during their shows. They were itching to do something more creative and fulfilling, and hoped that recruiting a keyboard player would add another dimension to the band.

Neither Fagen nor Becker could afford a car, so the first problem to overcome was how to hook up with the guys on Long Island. With Fagen toting his Fender Rhodes piano and Becker his Dan Armstrong Plexiglass bass, they took the Long Island Railroad out to Hicksville station where Dias and Thomas were waiting to pick them up. Then they drove to Dias’s house, where the audition took place in a rather cramped kitchen.

Just as Kenny Vance had been shocked by his first meeting with Fagen and Becker, the experience stayed with Keith Thomas for a long time, too. “Fagen looked like Jean-Paul Belmondo on acid,” he said. “He had shoulder length hair, he was real skinny and he had these Michelin tire lips, with his head jammed into his shoulders; he had a real hipster persona. Walter Becker, with his long blond hair and sunglasses, looked like a Nazi youth camp!”

Dias didn’t really have room for a band to rehearse so it became the norm for them to repair twice a week to Thomas’s basement at 43 Ellwood Avenue in Hicksville. At that time Thomas was working in the physiotherapy department of the local hospital, but working long hours at the hospital and rehearsing and gigging with Demian was taking its toll on him, both mentally and physically. He was dropping pills to maintain the pace.

By the time Becker and Fagen auditioned, Dias and Thomas had tried out about a dozen different bass players. “Each one was worse than the last,” said Thomas. “Although the ad had warned that no assholes need apply, just about every asshole applied. Guys would show up and play variations on Question Mark and the Mysterians’ “96 Tears” for about an hour and a half.” Becker and Fagen plugged their instruments in. “I remember thinking either these guys are gonna suck horribly or they are gonna be fuckin’ geniuses,” said Thomas. “And they proceeded to play 20 of the most original songs I’d ever heard in my life.”

As ever, the songs were taken from their black and white exercise book, the same list of demos they had already recorded with Kenny Vance: “Android Warehouse,” “Finah Mynah from China” (later to become “Yellow Peril”), “Parker’s Band,” “Soul Ram,” “I Can’t Function” and a song sometimes referred to as “Stand By The Seawall,” which would much later be adapted to become the middle section of “Aja.” Even at this early stage of their career, they had the chord structures and some of the lyrics to what would eventually become one of their best known compositions.

The longer the performance went on, the more Keith Thomas was impressed. “I was looking at Denny and my fuckin’ eyes were rolling in my head. Where the hell did these guys come from? And it wasn’t like they were playing variations on three chords; this was dense, interesting stuff, particularly at that time.” Once Fagen and Becker had finished running through their own compositions, they jammed with Demian for two or three hours.

Despite their apparent aloofness and introspection, Becker and Fagen were invited to join the band for their sensational songwriting skills. They had a discussion with Dias and Thomas as to what would be their battle plan. The pair may have had outstanding musical talent, but they were still surprisingly naive about the machinations of the music business and had no idea what to do with the songs, only that they wanted a recording contract. Certainly, Becker and Fagen were desperate for a break, but not desperate enough to consider playing live. They wanted absolutely no part of it; the thought hadn’t even occurred to them and if it had it would have horrified them. Becker admitted his naivete quite openly in an interview years later. ”They (Demian) worked in clubs and stuff, which was something we’d never heard of.”

The reasons for Becker and Fagen’s reluctance were firstly because they were unfamiliar with, and dismissive of, the chart hits of the day, secondly because they were looking for an outlet for their own compositions, and thirdly because the prospect of playing in bars and clubs where there were regular outbreaks of violence intimidated them to no end. They believed their strength lay in the songs which they had painstakingly composed. They bluntly told Dias and Thomas: “What do you want to play night-clubs for? If you need money, get a job. Otherwise: you’re just wasting your talent and you’ll never get to do what you really want to do.”

Dias and Thomas were frustrated for an entirely different reason. Whereas before they weren’t able to play their own material live, now they had what they considered great and innovative songs at their disposal but the composers wouldn’t play ball.

Dias and Thomas didn’t need much persuading to learn to play and sing Becker and Fagen’s tunes. In fact, another result of Becker and Fagen joining the band was that Dias and Thomas completely abandoned their own attempts at songwriting. Denny Dias had only been writing for a year or so and although he had no trouble with writing music, he was dissatisfied with his lyrics and neither did he have much faith in any of his erstwhile songwriting partners’ lyrical abilities.

While they had a full band to play their songs, they also had personnel problems. The other member of Demian, drummer Mark Leon, took an instant dislike to Becker and Fagen and made no secret of it. Becker and Fagen preferred a simple, straightforward rock and roll backbeat which did not subtract for the subtleties of their compositions; a player who was “neat” — heavy with his left hand and right foot. Leon’s drumming was too busy for them.

Denny Dias was a bebop influenced guitarist, which Fagen and Becker loved and which they could accommodate, and Keith Thomas had noticed how Mark Leon’s jazz leanings had been frowned upon during Demian’s live performances. ”Sometimes, during our version of “Cold Sweat,” he would announce, “In the middle of the fatback drum solo I’m gonna do Buddy Rich from West Side Story, and he’d go into that with all kinds of fuckin’ drum sounds and clear the room.”

Soon after joining Demian but before they actually recorded their demos with the band, Fagen and Becker demanded that Dias and Thomas fire Mark Leon·. They were never ones to do their own dirty work if they could get someone else to do it for them. When Leon was confronted with their decision he, in Thomas’s words, “went bananas, berserko.” He caused quite a scene, but Dias and Thomas had half-expected it, since sudden rages formed a normal part of Leon’s personality anyway. Eventually Leon’s rage subsided and he left peacefully. A few years later Fagen recalled the general dismemberment of Demian somewhat differently. “We used to chastise and abuse them, so they all quit. And so there was Denny and we’d ruined his band. So he had no place else to go.”

(Editor’s Note: Brian had always wanted to write a book on Steely Dan and we admire his persistence, patience and hard work in achieving his dream. However, we at Metal Leg have a couple of problems with Reelin’. Becker and Fagen refused to cooperate and, as a result, many stories are based on unverified third-person accounts and Brian gives them a lot of credence. Brian also didn’t give us a preliminary draft of his book. If he had, we would have .questioned some of his speculations and his choice of getting into some personal subjects that aren’t really anyone’s business. Despite our problems with parts of the book, it has many interesting parts and great photos, including several pics of a young Donald courtesy of his mother. This book should be part of a Dan-fan’s collection, but remember, just because it’s in print, doesn’t mean it’s gospel.)

The Dead Band Society

The following article appeared in the “Styles” section of the Sunday, August 15, 1993 issue of The New York Times as well as in other syndicated newspapers across the country. It was written by David Browne, a music critic who also writes for Entertainment Weekly and it profiles the history and workings of the illustrious publication that you are reading right now: Metal Leg. Since the article appeared a year ago, our subscriber base has grown by almost 50%.

Steely Dan’s back.

Readers of Metal Leg magazine

are very prepared.

What:

Metal Leg: The Steely Dan Magazine, a fanzine devoted exclusively to the sardonic ’70s pop band. It recorded its last album in 1980 and quietly disbanded the next year. “It”s all these things you wanted to know about Steely Dan but were afraid to ask,” said the editor, Pete Fogel, 34.

Why Ask?

Because Steely Dan never really went away. The band’s music — their hits include “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” “Peg,” and “Hey 19” — fits like an Earth Shoe on classic-rock and contemporary-jazz radio station formats. As a Presidential candidate, Bill Clinton played “Reelin’ In The Years” at campaign stops last year. Steely Dan CDs remain among MCA Records’ most consistent sellers; their fussily produced music sounds even more pristine in that format. Toss in the reclusive nature of the band’s leaders, the keyboardist-singer Donald Fagen and the guitarist-bassist Walter Becker, and you have a cult for the nostalgic audiophile.

Do It Again:

Steely Dan has made a typically odd comeback. This spring, Mr. Fagen released an album, Kamakiriad, his first in 11 years, and he and Mr. Becker have reunited for a 21-show Steely Dan tour — their first in 19 years — that arrives Wednesday at sold-out Madison Square Garden. “They’re the Lennon and McCartney of America,” Mr. Fogel said.

Reeling In The Dan:

Metal Leg, 22 issues old, was started in England by a devout fan in 1987 and taken over three years later by two subscribers: the gregarious Mr. Fogel, who also tends bar and books rock bands into Manhattan clubs, and Bill Pascador, 29, the low-key publisher, who is a media supervisor for an ad agency. Together, they crank out each hand-stapled issue on a weathered ATC computer in Mr. Pascador’s apartment on the Upper West Side. Metal Leg has roughly 4,500 subscribers, who pay $14 for four issues.

Pretzel Logic:

You’d think a magazine devoted to a band that hasn’t recorded since Ronald Reagan was elected president would have trouble filling its pages. Not Metal Leg. Each issue contains interviews with musicians fondly recalling licks they played on Steely Dan albums, excited reports of Mr. Becker and Mr. Fagen’s recording progress, and arcana, like reprints of old album reviews and Mr. Fagen’s 1965 high school graduation picture. “Many people will tell you Steely Dan never toured,” Mr. Fogel said, proudly explaining that the group had indeed gone on the road. “Not only did they tour, but we have pictures. We have reviews. We put that story to rest.”

My Old School:

In the ’70s, Steely Dan’s black humor, sophisticated jazz riffs and leave-us-alone mystique made nerds feel cool. Apparently, that’s still true. “Back in the ’70s, their audience had long hair and smoked pot,” Mr. Pascador said. “Now they’re married and have kids, and they’re living vicariously through our magazine. We get letters from doctors saying they play Steely Dan in the operating room.” Mr. Fogel added: “These aren’t little kids writing us. They’re professionals. I haven’t had one bounced check in three years.”

Why Metal Leg?

Supposedly, it was the original working title of Steely Dan’s last album, Gaucho.

Why Pete Fogel?

In 1975, the teenage Mr. Fogel was smoking pot in a friend’s house on Long Island, he said, when his friend’s older brother came in and played Steely Dan’s Katy Lied album. “This weird thing went through my body,” he said. “I can’t explain it, but it was a religious experience. For me, no other music has come close since. They were the filet mignon and lobster tail of music.” Mr. Fogel, who plans to attend ever show of Steely Dan’s tour, jokes that he has played Kamakiriad 500 times and is on his 47th copy of Katy Lied. Then again, maybe he isn’t joking.

No Static At All

Metal Leg is not authorized by Mr. Fagen and Mr. Becker, who also declined to comment on it. But they do appear to be bemused by its existence. “I met Fagen at a restaurant, and he said ‘This is the guy who does my fan magazine,’ ” said Mr. Pascador, imitating Mr. Fagen’s nasal drawl. “It was very painful for him to say ‘fan magazine.’ Then he looked at his picture on the cover and said ‘I look like Gomer Pyle.’ ”

Woodstock Warren

The following exclusive interview with Steely Dan tour pianist Warren Bernhardt was conducted for Metal Leg by one of our subscribers, James Harris of Saugerties, _NY. It is one of the best interviews we’ve ever printed and it also has the distinction of containing the most “1-800” numbers to appear in a single ML article.

I had the chance to interview Warren Bernhardt in early 1994 at his home in Woodstock, NY. Our interview lasted almost two hours and we covered a lot of territory from Fender Rhodes, to the personalities of the band members, to the intricacies of Steely Dan music.

Prior to the interview Warren told me that the best interview he ever read was one where Duke Ellington interviewed himself. The Duke was frustrated that interviewers never asked him questions he wanted to answer, so he asked the questions.

I went into this interview with a list of questions, but I allowed Warren leeway. Within the first 15 minutes he basically answered my list, but gave me insights that went far beyond any questions I could dream up.

Metal Leg- Not too many people know about your background. Did you see the Metal Leg that had the tour information? (ML Issue #22 pp. 4-5)

Warren Bernhardt- Yeah, it was wrong. First of all, let me do a disclaimer. Drew Zingg was the musical director, not me. I don’t know how they ever got that information. It was definitely a mistake. Drew was the guy … (Note: ML corrected the mistake in Issue #23)

ML- He was with Donald in the …

WB- Rock and Soul Revue. Which is where they hooked up. He’s a marvelous guitarist.

ML- Can you give us a little bit of your background, a little bit about you.

WB- I started playing piano very early on, and it was classical musk all through my childhood. Eventually I got into jazz while I was at school in the Midwest. I studied chemistry and dropped out to play jazz. l came to New York after that as a member of the Paul Winter Sextet. When it was first formed it was strictly a modem jazz group. We came to New York to record for Columbia. I moved here. Things were going great, then they slowed down. There wasn’t much work so I did whatever gigs I could. I practiced a lot, did club dates, you name it, I did it.

I worked with a lot of singers during that period of time, starting in the early ’60s. In the late ’60s I hooked up with Tim Hardin, who was a great singer and poet. I worked with him for a few years. He lived up here in Woodstock. So I came up here the first time to do a record with him and fell in love with Woodstock, which is why we’re here now.

While I was touring with Tim in California I met a woman and we had a son. I needed money, so I started working in the studios. It wasn’t what I had intended to do, but you don’t often get the chance in music to do what you really want and make a living at it. So I got quite active as a studio musician. During that time a lot of my friends had done work with Steely Dan, but I was never asked to record anything with them. I thought, “Gee, I’ll never be on a Steely Dan song,” so it was quite a thrill when they asked me to be on the tour.

Later in the ’70s I started doing my own records, started getting back to what I had originally intended to do, which was to be a jazz artist. I made several albums for Arista. Right in the beginning when they started making CDs, a company called Digital Music Products (DMP) asked me to record for them. I was one of their first artists, a little over 11 years ago. Finally I was doing my own records, which is what I really always wanted to do. I formed a trio, which is my favorite context. We worked some, went to Europe, played around the States. We made a few albums together. I have six albums on DMP now.

I did work with lots of singers through the years. I worked with Carly Simon, Liza Minnelli. I worked with Richie Havens in the ’60s. So I actually do have experience working with pop music and as an accompanist, rather than just straight-ahead jazz.

Last year I was playing Europe and Steely Dan’s manager called me then and asked, “Would you like to do a Steely Dan tour?” and I said “Yes!” So here we are.

ML- I read a review of your Reflections CD in Downbeat.

WB- You got it with you? I never read it. Was it any good? There was a good one in Jazz Times … (reading review) … Only three stars? I never saw this one, maybe I shouldn’t. I’ll get on this thing about critics. “…the trio tickles classic Evans…” What the hell does that mean? I think they mean “tackles.” Tickles. They don’t even proofread this shit. The really good reviews for that CD are in Jazz Times and Stereophile. They gave it a regular thumbs up. They said it was one of the best CDs of the year. I think it won an award in Germany for best jazz CD of the year.

ML- They played “Tuzz’s Shadow” on the Steely Dan tour.

WB- That was great! While we were rehearsing in NY, Donald said we need some “traveling music.” It’s for while people are coming back to their seats after intermission. It’s not really a focused thing, but after the intermission, while everybody’s out getting hot dogs or whatever. He said we needed a tune to play for traveling music, and rather than just playing a blues or a standard or something, he really dug this tune off one of my albums (“Tuzz’s Shadow”, from Reflections). And he played it for Walter. They both said, “Yeah, let’s see if Warren wants to do it.” So I wrote a quick arrangement for the saxes that we had, two tenors and an alto. Then we played it every night. It was great. In fact, my friend who wrote it came to the Greek Theater and he was really gassed. He was a friend of mine from Rochester.

ML- He co-wrote it?

WB- No. He wrote it. He wrote the tune.

ML- And you played it on your album.

WB- I put it on Reflections. I guess it’s a different kind of tune, and I think what Donald liked about it was that it had character. It has already been printed in The Real Book, a fake book for jazz musicians. They asked me to send them the right chords and my friend gave them permission to use it. It’s become like a little standard. A lot of people really loved it. They asked me, “What IS that song?”

ML- I was writing down the set list for the night I saw you and I didn’t recognize that one.

WB- A couple of times Donald came out and said “that was Warren Bernhardt and the Steely Dan Orchestra doing “Tuzz’s Shadow.” The way he says the “or-ches’tra” thing. That was nice. We would always go right into “Deacon Blues,” immediately after. Now there’s a great tune!

ML- On my way to the concert one of the Albany radio stations was there talking about that night’s concert. They said some of you came out and were playing some jazz tunes for the sound check.

WB- Donald or Walter would come out and just start a tune. It has got to be the only “pop” gig in the world where the leader will come out and start playing “Confirmation” by Charlie Parker or “Solar” by Miles Davis. The whole band just comes in on time. It’s just to get loosened up. Donald is very knowledgeable about those tunes. So is Walter.

ML- What was it like learning the songs? Did you have to pitch numbers that weren’t working or just by and large did things come together?

WB- Well, we rehearsed a lot more songs than we used. Originally I think we had 35 songs or even more. Gradually we weeded out a few during rehearsals. Then, we still had a four-hour show by the time we went to Detroit for the first concert. So the set was still in flux. I was hoping — I thought maybe that they’d change it every night and make it a little different. But I think some of the songs were too long, they made the show too long. I’m not sure, either Donald or Walter, whoever was singing, didn’t feel quite as comfortable on some songs as on others. Maybe the band wasn’t playing some songs as well as others. Gradually they began to be weeded out. About the time of the sixth or seventh concert, they set upon an order that they pretty much stuck with the rest of the tour. It seemed to work well, to be the right way. It seemed like both Walter and Donald were enjoying the way they sounded on those tunes that were kept. There are problems only singers know about, problems the songs present, range-wise, remembering the flow of the poetry and stuff like that.

So it gradually settled down and we played that show for the rest of the way out. If you heard us in Saratoga and then came back and heard us again in Albany, it would have been basically the same sequence. Maybe a few changes in the order they put the tunes in. For a jazz guy, that was a little strange for me. But I can understand it completely. But with my own trio I try never to repeat the same show twice. But when I was with other bands like Steps Ahead or on other, bigger shows, if we did two concerts on the same night we almost always played the same show twice. I guess it just has to do with the concept. The smaller group — the trio — is much more wide open, and flexibility is the key. But this was never boring, the music was too good to be boring. In fact, we had a lot of chances to solo, so you could get variety that way. There were little holes for me to fill in, too … and the solos would of course change from night to night.

ML- Were there different encores? I know you played “My Old School” when I saw you.

WB- We always did that, and often we would play “F.M.” I don’t think we ever did three encores, although we had rehearsed some. On “F.M.” the band would sometimes vamp and Donald and Walter would leave the stage. It was pretty cool. Sometimes if Donald’s voice was tired, or they were in a hurry to get a flight, we’d just play on without them.

Thinking back now, there were some songs from Kamakiriad that we did. Not as encores, but I just thought of this. We had “Trans-Island Skyway” and “Springtime” that we played at the first few concerts. I remember at Madison Square Garden we played “Springtime” for the last time. I love those songs. And three more of Walter’s songs from his new record that we rehearsed and I thought we were going to do every night — “Girlfriend,” “Our Lawn,” “Sweet Little Cringemaker,” and maybe even one other. We dropped those. At one point we were going to do “Kid Charlemagne.” We got the music and everything. Even scheduled a special rehearsal, and then they said they wanted to keep the show the way it is. Evidently, the show that we were doing by then felt really comfortable for the guys. I know it felt great to me.

ML- You have enough songs that if you want to go on tour again you can get a different mix of songs.

WB- We are going out again! In April. Let’s talk about that. We’re going to Japan — Tokyo, Osaka, more. There are rumors that we might be going to Europe also, too. It was just a suggestion I heard. I don’t think that’s at all finalized. Maybe the States again, too. There’s still a lot of cities in the States where we didn’t go — Minneapolis, Denver, Seattle, Portland, San Diego, New Orleans, more.

ML- What do you think prompted them to want to tour, nostalgia?

WB- Oh, I don’t know what prompted it — but I’m sure glad they did. In the music business it’s usually a combination of things. It’s a business — money, sales, things like that. I know for sure that touring helps, but you have to feel ready to do it. I doubt if it was nostalgia, although it may seem that way to some of the fans. Wasn’t that covered in the interview in Musician magazine? Or Rolling Stone? I guess 19 years is long enough. I do know they didn’t want to go out unless everything was done right. The right sound company, the right lighting, the right crew, the right band, the right promotion, you know. It was the rightest thing I’ve ever been involved in! Usually there’s some awful problem or screw-up or something doesn’t work, or people don’t get along. I was actually crying when this thing was over — hugging one another — I didn’t want it to end. We had so much fun that I for one didn’t want to come back home quite so soon.

ML- How did the rehearsals go? Were they long and tedious or did you get things done quickly?

WB- Well, they planned a lot of time. You talk about doing things right. We had over three weeks of rehearsals. First there was just the rhythm section: Tom Barney on bass, Peter Erskine on drums, and myself, and of course the musical director, Drew Zingg, on guitars. We worked for three days, just the four of us, learning the charts and running through all of the songs. We actually got down “Josie” and a couple of others pretty good. Donald and Walter weren’t there yet.

Starting the next full week, the horns showed up. People started coming in. Two days later Donald was there and by the end of the week so was Walter, and then the background singers. It all came together by pieces. By that time the rhythm section pretty much knew the stuff, when we were pretty sure we had it correct. It was very precise. By the time you got done rehearsing, you knew exactly what your parts were for each tune. Then it got to the point when they began figuring out what the actual sets would or could be.

By about the third week we were actually running down the show, which of course was way too long. And those rehearsals got real long for me. My hands were really hurting bad. We rehearsed from 1 to 7, sometimes earlier or later, and for one week near the end I was doing another record date in the morning, and even another set of sessions at night. Afterwards, I was completely exhausted. But, of course, that was my own fault. It was a matter of prior commitments I had to do. I’m not sure that everyone went through that kind of ordeal.

The very last week we went to Detroit and had real production rehearsals at Auburn Arena, with the lights, sound, and the full stage. We rehearsed all evening for three nights, and that was it. I never found it to be tedious. It was exacting and it required a lot of concentration and it was fun. There were breaks and things. But it was work — really satisfying work.

ML- The results were good. Supposedly a live album is coming from that?

WB- Well, that’s another whole thing. By the time we got to St. Louis or maybe Texas there was a big digital multi-track machine. I think that everybody’s sound went into it directly, without any kind of EQing. Just pure signal. From then on I think they recorded 10 or 12 concerts. I guess they may be listening to the stuff now. I don’t know what their plans are. I guess if it’s good they might release something like that. But I have no idea. Of course it’s up to Walter and Donald. It would be fun, though. I’d really dig it if they put out a live tour album. It wasn’t just a tour. It was a historic tour. That’s what’s so special about it.

ML- For die-hard fans, it’s like the Beatles getting togelher.

WB- I know. That’s why it was so great. And the reception, the fans’ reception. It was like nothing I ever witnessed before.

ML- How did you hook up with these guys? Did you know them for a real long time?

WB- No, not really. I think it happened mainly through Donald. I think he heard me play and then he got to listen to some of my recordings, and I guess he must have liked what he heard. He probably then played them for Walter. I can only guess about that. Who knows?

ML- You were in the right place at the right time.

WB- I was in the right place at the right time. And, of course, I’m an experienced musician with something to say. However it happened I’m very glad that it happened.

ML- I don’t know if you’re allowed to talk about this, but are you planning to do any future recordings with them?

WB- I don’t have a clue. In fact, I would guess that the way Walter and Donald usually record, I don’t think that they’d ever use a set band, with set personnel to make an album. They seem to bring in musicians according to what they think they want for a given tune. They look at the song and see what or who might sound good on it. Plus I really have no idea of their plans, if any. Also Donald mentioned to me that he’s starting to get into sequencers as well, electronic instruments, so that would change things, too. I have no idea, really.

Of course it would be a gas if they’d do something new with this band. You’ll really have to ask them, I don’t know much. I know that Donald has been helping Walter with his new album, co-producing and co-writing some tunes — we do “The Fall of ’92,” that’s a great one — and of course; Walter produced

Kamakiriad. So both of their albums are almost like Steely Dan albums. But as far as going into the studio and doing a brand new Steely Dan recording, I have no idea. I hope so.

ML- I’ve got everything — from the first movie thing they did — You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It, Or You’ll Lose That Beat.

WB- You’ve got everything, the whole thing? You know, I was in France the very day they called me. I was at this guy’s house for dinner. He wasn’t in the music business. A friend of a friend of mine, he worked in advertising or something. I mentioned that Steely Dan had called me that day and asked me to tour with them. This guy Bruno went apeshit crazy. It turns out he had every Steely Dan album. He knew the lyrics to all the songs! He spoke very little English but he knew every Steely Dan song by heart. I said to myself, “this is something, to meet a complete stranger in the middle of Paris and he knows the entire repertoire and their words.”

Jan, my wife, hadn’t heard the group until we came to Hartford, which isn’t far from here. Everybody sitting around her in the audience knew all the melodies and the lyrics to the songs. She couldn’t believe it. “They were singing all the songs with Donald,” she said. I said, “Yeah. There’re some real hard-core fans out there.”

ML- I was surprised at the song selection. I would have never thought that songs like ”Third World Man” and “Babylon Sisters” would fly in concert, but they were fantastic.

WB- Yeah, they worked, and for a while we were doing “True Companion,” too. Evidently that was a little slow for the show, and it was very difficult to get it together — the vocal parts are extremely difficult — but it’s a great arrangement of a unique song, and it had some beautiful stuff between the piano and the vibes. I thought it was interesting having vibes on the tour, It was really a nice sound — very distinctive.

ML- I was surprised you didn’t do “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number.”

WB- Or “Do It Again.” Well, I read in one interview that Donald doesn’t want to sing that anymore. He was very definite about what he did and didn’t want to do.

ML- You get tired of them, I guess.

WB- That’s another thing I’m not sure of — why they selected just what they did. I’m pretty sure that they chose the songs they most felt like performing at the time. I think it was pretty cool, — the show, I mean. It would have been fun to do “Kid Charlemagne,” maybe “Black Cow,” or “Sign In Stranger” … and there were some others with really great piano parts. What’s the one with a girl’s name? “Maxine.” That was on the original list of songs for us to listen to and learn before we began rehearsing. I said, “Oh boy, this has some great piano on it.” Then we received further communication that said “Drop Maxine.” But take

“Babylon Sisters.” There’s a chord progression in that song which I think is as good and as interesting as anything that’s ever been written in jazz history. It’s very harmonically sophisticated progression. It’s when you get near the end of each verse, just before “and the lights across the bay” or “as he watches his bridges burn” (hums the passage). It’s beautiful, that progression.

I just got done doing a fascinating project. Donald asked me to be the host and moderator on his new educational video, which we just completed last week. He takes the blues and he shows how they enter into five of his compositions. So first we did a blues in A and talked about it some — the basic structure, the harmonies. Then he did “Chain Lightning,” which is closely based on the blues in A, and which has been slightly disguised harmonically so that it doesn’t go quite the same as a straight-ahead blues. And then he tells how he derived the changes and what scales he used to play on them. And then we talked about “Peg,” which is a different kind of blues. Each verse follows a twelve-bar blues structure, but there are major 7ths all over, and of course, there’s a chorus.

Then we covered “Josie,” which is based on a kind of “swamp blues” and we talk about that and play it together. We played all the tunes on piano and Fender Rhodes. And then we took apart one of the greatest tunes from Kamakiriad called “On The Dunes,” which has some horribly difficult chords in it. It’s like a blues-ballad. We talked about that tune a lot. It has a nice harmonic flow to it. And then we finished up with “Teahouse On The Tracks,” also from Kamakiriad, which really doesn’t sound like a blues when you hear it, but it is based firmly on blues roots. Once you play it you begin to see how that’s true. It’s called ‘Concepts For Jazz/Rock Piano. I was kind of a straight-man for Donald on this one. It was a new gig for me to be the straight-man. It was fun. He’s a very witty guy, bright, funny, a joy.

ML– Did you know Peter Erskine prior to the tour?

WB- He’s played on several of my CD’s and we played together with Steps Ahead for a few years. It was a real joy to connect up with him once again. I figure it’s been very cathartic for Peter, too. He’s been playing a lot of “chamber jazz” for a few years now, getting more and more into it, and here’s this gig where he can really get down and bash and play some solid grooves. He’s one of the great drummers in the world, you know — can do everything beautifully. He really enjoyed it. I know he did. I know I did.

ML- It’s really hard to figure out what the appeal is, besides people just enjoy it.

WB- Well, they’re geniuses to begin with, and maybe people do just enjoy it.

ML- The music makes me think. I have to pay attention and focus on what’s going on.

WB- I just think the music is fascinating. And lyrically, the poetry is sometimes off the wall… beautiful. There are always lots of things to think about it in the songs. You mentioned “Third World Man.” You were surprised that they chose it?

ML- Yeah, I was for some reason.

WB- Wasn’t it great?

ML- Yeah, that’s the thing of it.

WB- That was one of my favorites every night. It has such a mood about it. How did you like the overture?

ML- Oh yeah, you started with ”The Royal Scam.”

WB- Then “Bad Sneakers” and “Aja.” “Peg” was part of the overture for the first three or so concerts, actually. I think when we got to Hartford Donald said ”Let’s do ‘Peg’.” We had been doing “Bad Sneakers” with the vocals in rehearsals. So the two just got changed around.

But about their music. Some people beard it a little different. It’s hard to put a finger on just what the appeal is, except that it’s good music.

ML- Especially when you look at some of the music that’s out there. My stepdaughters are into the rap music and stuff.

WB- Is that because we’re getting old or something? I just don’t get rap. My daughter was into it for a while. She must be growing up, she’ll be 15. The other day she was listening to Billie Holliday. Thank God. I can see if you come from the ghetto, from the inner city kind of atmosphere and you’re black and you’re young. Yeah, then rap is your stuff. You do it. It’s important to you. But for me, I think it lacks so many of the things that I love about music — like melody, harmony, big things. I’m a harmony freak. That’s another thing I love about Steely Dan, the harmonies. I don’t know about rap. I must be getting too old.

ML- I find myself saying to my kids, “Turn off that garbage.”

WB- But to them it’s not garbage. It’s being sold to them as being great, even though I’m not at all sure that it is. Maybe something great will come out of it. The same way that jazz came out of the black neighborhoods in New Orleans. I’m sure that many of the folks who first heard jazz music hated it, as much as we hate the worst rap stuff, but look where it led, at the great music that grew out of it.

ML- I like synthesizers, but the way they use them in rap music, that it’s the whole basis of the music, instead of incorporating them.

WB- There are some bands now that use live drums. It makes a big difference. At least there’s a live interjection. They seem to use collage a lot, too. They will cut out two bars of a Miles Davis solo instead of coming up with something new themselves. It’s more like a two-dimensional representation.

ML- There’s a rap song out now. I can’t think of the name of it, that has a few bars of “Peg” in it.

WB- I heard that. I remember hearing it on the tour bus. Didn’t they use various Steely Dan tunes?

ML- That’ s the only one I heard, but it wouldn’t surprise me.

WB- There are a lot of bebop influences in Steely Dan. That progression, the introduction to “Peg.” Those influences happen in quite a few places. The solo on “Teahouse On The Tracks,” which I got to play every night. Cool song. I lay into that one. Those things are really jazz oriented, and bluesy, too. I’m not sure what else Steely Dan fans would like to hear about I’m trying to think of some funny stories, things that happened. You know, Walter has a great sense of humor. He was always coming up with funny stuff, masterful one-liners.

ML- I understand they don’t like to be interviewed.

WB- Well, I know they did a lot of interviews for this tour. I think the best one I read was in Musician (September 1993). They were on the cover. It was some pretty off-the-wall conversation. I liked what Donald was saying about what he calls “laser thought.” I know what he meant and could see it working. I learned a lot by just being around those guys, Donald in particular. We were fairly close together on stage and I paid really close attention to him, mainly, and of course the bass and drums. We shared the Fender Rhodes, and for the first part of the tour he was playing the acoustic piano, too, and I felt very connected to him.