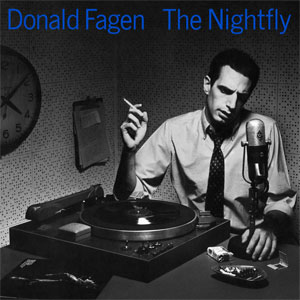

Richard Cook meets the urbane spokesman of cool, Donald Fagen, who, for 14 years, partnered Walter Becker in Steely Dan. A celebrated eccentric, Fagen is now experiencing international success with his own solo career and the LP, The Nightfly.

Originally published on January 22, 1983

By Richard Cook

New Musical Express

In person, it seems like Donald Fagen is himself a serious case of miscasting.

It’s hard to equate this hunched, rather shy and inconspicuous figure with the cocksure, crackling wit and urbane spokesman of cool we’re familiar with from the slim library of Steely Dan records that notate ’70s America.

It’s hard to equate this hunched, rather shy and inconspicuous figure with the cocksure, crackling wit and urbane spokesman of cool we’re familiar with from the slim library of Steely Dan records that notate ’70s America.

Fagen has the aura of heavily acquired wisdom about him, permanently aware of folly, wistful about wasted effort, a sceptic not so much stung as wearied into indifference by the cut of it all.

As it turns out, Fagen is probably one of the great scholars in American pop. He prizes the constructive use of knowledge. I don’t quiz him about his favourites: specific faces and profiles don’t seem to concern him.

As he talks, in a thoughtful lecturer’s voice devoid of specious excitement, the impression grows that Fagen knows exactly what matters about music, what ticks at the heart of pop’s name game and why it is able to find a corner for a man like himself, past 30 and a branded eccentric.

And more than a corner – The Nightfly, his recent solo record, has put him in a spotlight on his own for the first time.

In fact, Fagen is neither the eccentric nor the nerveless cynic that might be expected. His satisfaction is in creating music of genuine substance.

However oblique the reputation he garnered with Steely Dan, it’s a concern for intelligence which pervades his interest in pop composing, not some wayward boho deck of mannerisms. It’s feasible to criticize The Nightfly or any of the Dan albums as being excessively cold because they’re crafted with such rigorous thought that the rehearsed delirium of, say, Springsteen’s rock’n’roll is at least a universe away.

But their dynamic power is unassailable. Their co-ordination is itself a pleasure. The playing of the music is a thrill on its own – and that is a rare strain indeed among pop musics.

Fagen disowns the early Steely Dan records as incomplete trials, although it was that very quality of spontaneous experiment that made them so exciting: here was a melting pot of brilliantly characterful players of extremely diverse temperament fashioning pop music out of intellect instead of stamina and muscle. As the group itself became subservient to the writing platform of Fagen and his erstwhile partner Walter Becker, the music slowly dried out, to the point where Gaucho, the final Steely Dan record, seemed like a bloodless computation of Can’t Buy A Thrill.

The Nightfly represents the complete rehabilitation of Fagen. Its series of freshman vignettes, flirtatiously presented as quasi-autobiographical, has all the hallmarks of the finest Steely Dan records – the unexpected lyrical tang, the brooding jazz-informed harmonic sense, the buoyant update of past popular forms – allied to a deeper personal intrusion than Fagen would previously allow himself.

Although he still claims detachment, it’s clear there is more of his heart in this record. That it is presented in the currency of mainstream American pop (the rollcall of sessionmen, the flawless studio resonance and cunning understanding of the motion of chart music) only adds to the enjoyment of watching this awkward, introverted Easterner taking on the higher echelons of US music and introducing a personal sophistication to large scale acceptance. The irony of this success – crystallised perfectly in the complex but deliciously lilting retread of “Ruby Baby” on the album–is a coup de grace to savour.

“Interesting” is probably how Fagen would describe it if it were the work of another. He chooses his compliments with care, picks through an extensive vocabulary with quiet deliberation, I ask him if he thinks himself reclusive and he says no; but I think he likes to be no more than the onlooker, at most.

We met at one of London’s least changed of old institutions, Claridges Hotel, one drizzly December afternoon – a piquant setting for a man fascinated by old Europe. This is what we said.

Where do you live now?

New York.

Is that your favourite part of America?

New York’s not really America. It’s more European or cosmopolitan. Certainly more than Los Angeles which is more like adjacent suburbs, no sense of an actual city. I lived there for a while and then moved back to New York.

Why did it take you the time it did to come up with The Nightfly?

I’m a slow writer. It took eight months to write and a year to record – there were lots of technical breakdowns with the digital equipment.

The cast of players is very much in the LA session format.

Well, we did the tracks in Los Angeles and worked on them in New York. I knew exactly who I wanted, stylistically, for each tune and I’d worked with them before. There are some new musicians out there who I thought were good, like Greg Phillinganes.

There is quite an interesting jazz-oriented underground on the West Coast – players and arrangers like Noel Jewkes. But why’s your own playing so little in evidence these days?

Actually there’s a little more on this album than lately. But the reason is that if I book these musicians and they can play the part I write better than I can, I let them do it. Then I can just sit and listen.

The style of the record puts it in what is pretty much a non-jazz environment but its being expended on writing is very much informed by a jazz sensibility.

Yeah, the kind of harmonies and chord progressions are from jazz, but it’s pop instrumentation because that sounds good to me. A lot of electronic instruments displace horn sections. The jazz I listen to these days is mainly my old records –I don’t hear that much new stuff that interests me. I think jazz died for me sometime in the mid-’60s. The vitality shifted into pop music and never went back into jazz. The form has been absorbed into their things. Sometimes I think the history of jazz is like a 50-year microcosm of Western music in general – classical form, romanticism and then chaos!

Mmmm… but, like, Rollins is still great.

Oh, y’know, these guys who are maybe doing glosses on their old styles are still great improvisers, but as far as new forms are concerned I don’t hear much… a lot of what’s called free jazz sounds no different from the ESP records of the ’60s, Albert Ayler and such.

What made you want to write about The Nightfly America rather than America today?

This is a parallel between America of that time and America today. It’s relevant culturally and, to a certain extent, politically. The main reason is that I’m 34 and I started thinking about why I became a musician. I was headed toward a different kind of life, really, maybe an English teacher or something like that. I studied literature at college and basically had my course set out for me. When the ’60s came along I perceived that there were other options and, since music was my hobby, I decided to try and make a living at it.

I used to live about 50 miles outside New York City in one of those rows of prefab houses that all look the same. It was a bland environment. One of my only escapes was late night radio shows that were broadcast from Manhattan – jazz and rhythm and blues. To me the disc jockeys were very romantic and colourful figures and the whole hipster culture of black lifestyles seemed much more vital to a kid living in the suburbs as I was. A lot of kids went through the same thing, although I guess as I listened to Jazz I was in a minority. That’s why there was an explosion of hipsterism in the ’60s, although it turned into something else.

Is it fired by nostalgia or bitterness or regret or…

Probably both the first two. I don’t know about regret. Certainly it was a more innocent and idealistic time. ‘I.G.Y.’ is a child’s view of the future with technology solving the world’s problems, a gleaming future. Very little of that came about and we’ve also found out that technology creates more problems than it solves. I guess I just wanted to look back.

Which of those “fantasies” that the record deals with have you come closest to realizing?

Well… I guess the recording studio, from a purely technological handle, reflects my interests from that time. It’s very high-tech and you have all these machines to play with. That’s how I imagined life to be. But I guess most of them just dried up.

Is a particular atmosphere conducive for you to do good work?

I like living in New York City because it’s inspiring that there’s a lot of action on the street and a whole range of music to listen to – although I haven’t found anything very new or interesting… but the whole environment is conducive to ideas. When I’m writing I just shut myself up in a room. It’s quiet. The pre-production is always so important.

Perhaps the very literate nature of your work tells against you in a pop environment that tends to thrive on stupidity.

Since there isn’t much going on as far as the lyrics are concerned in most pop music, that to me is an attraction.

Not just the lyrics.

Yeah, the same applies to the music too. Most pop today, I guess, is mainly very modal and static. I suppose it’s a novelty when people hear moving basslines and harmony.

Can you give us your explanation of the demise of Steely Dan?

After 14 years of working together Walter and I felt we needed a break from each other. Frankly we thought that the last album (Gaucho) was sort of, uh, lacking in spark. He’s doing some production work for Warners now. We may work together again, I don’t know. I’d like to do another solo album but we’ll see what happens. 14 years is a long time, longer than most marriages survive these days. I think we had a very lucky run of it.

Which elements of Steely Dan do you most want to retain?

I don’t really think retaining things from there. The style was developed over years and I don’t think about preserving the style, just the quality of work. I won’t stray too far from my background, I know.

I liked some of the later albums. The earlier ones were premature in a way. Most people break in a style playing live and so forth, but we just went in and made the first record and it clicked. We were doing experiments in public and they sound weak to me. Aja was a good record. I never think about it as a great body of work, though.

What can you do now that you couldn’t in that context?

This album is vaguely autobiographical – I think it’s possible to be more personal and subjective when you’re working by yourself. Walter and I had a collective identity. I still try and maintain a distance but it has to be more personal too.

Do you see yourself with a particular position in the American rock hierarchy?

It’s bizarre. Coming out of jazz, it’s different from the way most groups go. They start with very little musical knowledge and have different theatrical values. I’m not even sure what kind of music it is I do. I suppose you’d have to call it rock’n’roll. I think all the other influences lend a complexity that pop music doesn’t have, though. Although irony seems to be the perspective through which most people see the world these days, whether its in pop music or whatever, and as far as attitude goes a lot of people have caught up with that.

Do you think it’s a good trend?

A good trend? Well – I think it’s good to be objective and realistic and have a sense of humor about it. It can be a little… rich, sometimes. When you start to deal with high irony, making what people do trivial and their lives in order to view things at an extremely cynical level. I guess – I remember this from an essay I read, although I can’t recall the source – I guess that’s what they call decadence. It’s not very healthy, but then these aren’t the healthiest times in which to live.

That’s a charge that a lot of people might hold against you. To make a virtue out of cynicism.

Yes, but I don’t consider myself very cynical. I try to be as optimistic as possible. I’m probably quite skeptical. But if you transcend it with humor – if you act and do something in the world, hopefully you can maintain a healthy attitude.

Would you say you wrote as an observer or a participant?

There is always a certain detachment. The songs have characters and when I sing I act out a part. It’s not confessional, a Jackson Browne singer/songwriter kind of thing. My note on the album was intended to make it clear that it wasn’t exactly what happened to me. Just a picture of my life.

Are you suspicious of the confessional?

Suspicious? Well, um… suspicious. Not really. I take that kind of writing at face value… no, not suspicious. It can be self-indulgent sometimes.

I started with a group called Jay And The Americans. They did Sicilian numbers like “Cara Mia,” ethnic type numbers. I liked working with them quite a lot.

I also had a staff writing job at ABC Music where we were supposed to write songs for other people, although very few were done; they were usually a little strange for other artists. They were the kinda things we did later. We did a few straight-ahead pop tunes – Barbra Streisand did one. But our skill at that was… deficient, I think.

Gore Vidal said shit has its own integrity – not that all that music is shit, but our hearts weren’t in it.

Do you propose to do any work for films?

Not so much in scoring because you’re under the director’s whim – he could chuck it all out if her wants. And a lot of music is just incidental and not interesting to me. But where the music is a real part, where it has equal status with the images… except nothing like that has really come along. I did a short piece for Martin Scorsese’s King Of Comedy, an instrumental piece for David Sanborn. That was fun.

I turn down plenty of things. They want title songs for movies with silly titles or underscoring for suspense movies which is… hack-work, or synthesizer ostinatos. Which is just so easy to do.

Are you prepared to do any live performances?

No. After touring in ’73 and ’74 Walter and I decided to get off the road because we disliked touring. I might do some club work in New York or something, but definitely no touring.

As someone with an extensive interest in Europe, do you feel trapped by Americana?

I like living here. But as far as subject matter is concerned I would like to write about other things. This album was like something I had to get out of the way and it was therapeutic in some ways – “look at all this American stuff” and exhaust the subject matter.

Are your afraid of the success spiral?

Well… l haven’t felt it that much. The spiral hasn’t really swept me up. I don’t feel I have to top what I did the previous time. Aja sold five or six million records and it doesn’t bother me that since then I haven’t come anywhere near that. I’d be content writing for a small audience if I could still make records.

There is a danger of falling into a kind of lethargy – of slipping into making a stylistic mannerism of Nightfly music.

You always have to be careful not to repeat yourself. I can’t see myself making a spinoff (sounds disgusted) of what I’d just done, a standard pop music trick. But everyone only has one idea and it’s a matter of finding different ways to couch it. There ‘s a limit to alliteration without falling into pretension or following trends or acting like you’re part of a sub-culture when you’re not.

Do you think it’s worthwhile or at least possible to diagnose a society’s ill in music-making?

Not directly. I don’t think overtly political music or music supposed to evince a moral sensibility makes for good art, if you will. You have to create your own reality and try to express it as clearly as possible. I don’t try to create moral fables. Not that the ends of any kind of art shouldn’t be positive – you should be able to learn something or feel differently. But there’s no missionary objective.

You hear intimations that something may happen in pop music. With the technology that’s available you’d think something interesting would happen. Even with what I was saying about technology I think it’s probably still the main hope for music at this point. There are new ways to accomplish things – altering natural sounds or synthesizing sounds. Patterns that it would be impossible for the human brain to conceive. Something interesting could come out of it. But pop is always held back by its rigid rhythmical structure. It holds back the new things, although I guess that’s why it’s liked. That’s why it’s pop.

Maybe pop music will be over soon, like jazz.

In which case it will evolve into something else which isn’t.

What kind of person has this business made you?

Let me think about this for a second… it’s very hard to answer because it’s hard to know what the other possibilities were. I’ve been in pop all my adult life. It’s hard to think there’s another way to be.

One of the best Fagen interviews ever.

He definitely is working on a higher plane than your average “rock star”. It’s interesting that Donald went into full on hibernation shortly after this interview and really didn’t emerge again until 1991’s Rock N’ Soul Revue. Those lost years would make a great movie – or book.