Originally published on Nov. 28, 1980

By Boo Browning

Washington Post

It’s a little side street that’s closed to traffic so we can play there. No one else wants to come and play, ’cause we’ve got the basket tilted. — Walter Becker

There’s more than a tilted basket on the street where Steely Dan play. For a decade they have managed to break nearly every rule in rock and remain at the top of the league. When the pressure is on for simple chord structures and rhythm patters, they respond with bop, swing and jump; when the fundamental convention is “moon/June/spoon,” they unleash a combination of literary trick shots. And when all the other teams take to the road, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen refuse to get on the bus.

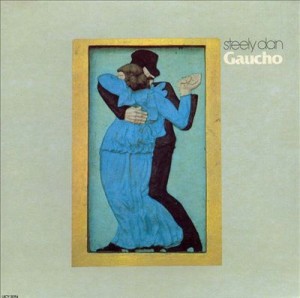

Now comes Gaucho, Steely Dan’s first collection of new material in three years, and the next sound you will hear will be the collective sigh of a hundred other rock groups aching to play the game, if they could find that side of the street. The best among them have sought it before — Billy Joel’s 52nd Street and the Eagles’ Hotel California come to mind — but the less-talented tend to hide out in the alley and wait for the big boys to go home.

Now comes Gaucho, Steely Dan’s first collection of new material in three years, and the next sound you will hear will be the collective sigh of a hundred other rock groups aching to play the game, if they could find that side of the street. The best among them have sought it before — Billy Joel’s 52nd Street and the Eagles’ Hotel California come to mind — but the less-talented tend to hide out in the alley and wait for the big boys to go home.

Through music that is instantly accessible but almost impossible to imitate, Becker and Fagen spin sardonic tales of winners and losers in language that’s often the cruelest, sometimes the most compassionate in the rolling lexicon of rock — dark progressions that resurrect bop’s undead with ghoulish glee. Eluding jazz and rock genres, their style incorporates both, with a literary leer that has contributed to their reputation as chicken hawks in an industry created for peacocks.

“I think we’ve always had a lot of sympathy toward the characters that are depicted in the songs,” says Fagen, leaning back on the stained yellow couch in his New York hotel room, “but apparently a lot of people don’t think that’s true.”

“There’s a mixture of something like a sneer and a tear,” admits Becker. “There’s something fatalistic about their possibility of surviving, of riding happily into the sunset. People are really exercised about one particular thing, and that is themselves. They will bore you endlessly with their broken hearts.”

On “Gaucho,” there are fewer broken hearts. Grotesques still inhabit the tracks, but they possess a wistful quality more appealing than pitiable.

“Sometimes it comes out that there are more tunes at a given tempo, or there aren’t enough sneers per tear,” says Becker, “but it’s an accident rather than an actual trend. We could get back on the track. We could be bum-burners again.”

Yet it’s not just the lyrics that let them assemble a variety of musicians (Gaucho features more than 35) and influences from song to song and still produce a sound that’s unmistakably Steely Dan. Pressed to describe it economically, Fagen uses the term “botanical Nazism,” and Becker has called 1973’s Countdown to Ecstasy” “Grateful Dead Meets Ferrante and Teicher.”

“Even though we use different musicians, they approach it with amount of enthusiasm,” says Becker. “You can tell when someone’s at the top of their game, overachieving. We also suggest things. There’s a lot of guidance in the improvisations. We set up arrangements so that a soloist will solo over a chord structure related to the overall structure.”

“We haven’t invented everything we’ve ever done,” Fagen interjects. “We’ve borrowed ideas, but they’re good ideas. They may sound fancy, but not contrived. We have different values from most rock and roll composers.”

“A lot of it is derived from music that the vast pop audience isn’t familiar will,” continues Becker, “music from the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, jazz, traditional big-band jazz techniques –”

” — which we have no knowledge of –”

” — which we have little knowledge of formally, but we’ve managed to get enough information about it so that we can adapt them to our own purposes.

“People don’t cover our songs well, is the funny thing. Most people don’t want to cover our songs, they’re reluctant to take some of these attitudes. But when they do, they make it sound like a worse idea than it was in the first place. Even “Dirty Work,” which I think we didn’t execute well, everyone else executes at least as badly as we did — which is inexcusable — and usually worse. I haven’t heard a good version of “Dirty Work.” There should be one.”

Becker sucks his frozen pop and shifts the crutches which have kept him in action since a car him several months ago. He lights a cigarette. “Somebody that totally wanted to do what we do would be crazy. There’s no need for two of us; it’s a shame that there’s one. It would be like two Thelonious Monks, right? Thelonious Monk has figured out that there’s not need for any Thelonious Monk, and he’s behaving accordingly.

The impulse to define Steely Dan’s music is a reaction to the ethereal, dreamlike quality of their songs. The adventurous will listen to songs like “Chain Lightning” and “The Caves of Altamira” again and again, trying to confront or focus on the elements that unsettle or disturb.

It seemed inevitable that, in an effort to tie their elements to something tangible, someone would cite William S. Burroughs as the underlying impetus for all Steely Dan music. After all, “Steely Dan” is the name of a certain erotic device in Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, and Burroughs shares with Becker and Fagen an ability to plumb imaginative depths.

Several years ago, the now-defunct New Times magazine published an article that sought to lay bare the mysteries of Steely Dan by inferring inextricable parallels with Burroughs’ works. Becker’s and Fagen’s lyrics were dismantled phrase by phrase and they conceded that yes, certain of Burroughs’ ideas had inspired them. Burroughs was ferreted out to listen to their music and conceded that yes, they were an interesting and enjoyable rock band.

It had the ring of rock mythology, a Paul-is-dead theory for the literate, but, like that myth, it served only to obscure the thing further. Paul McCartney wasn’t dead, as it turned out; the Beatles were. And Becker and Fagen insist that the New Times piece made a lugubrious mountain out of a literary molehill.

“That was purely the conceit of the author,” says Becker. “He insisted that there was an intrinsic connection. It made us feel futile.”

“He came to interview us and he had already formed in his mind a certain relationship between us and Burroughs,” says Fagen. “We kept insisting there wasn’t anything to it, but apparently there was nothing we could do about it. From the sound of the Burroughs quote, he must have tied him to a chair and made him listen to the record.”

“Or perhaps plied him with drink,” adds Becker sardonically. “Although now I do have plans to have Thanksgiving dinner with William Burroughs, as a matter of fact. My girlfriend knows him. I’m informed that he’s personable. Alienated.”

As far as their own literary endeavors, Becker and Fagen say they will stick to lyric sheets, with no plans for a book.

“I think about it sometimes,” says Fagen, “but I have no talent for that sort of thing.Too lazy.”

“I was planning to write a novel last night,” jokes Becker, “but damn if I could get very far. I’m serious, too. I was looking for a crack where a novel should be, and there wasn’t one. I wish I could. I wish somebody could.”

Both avoid emphasizing the literary aspects of their work, perhaps because they don’t want their audience restricted by age or intellect. In fact, the subject of age emerges rather comically in “Hey Nineteen,” from the new LP.

“We have both cracked 30,” says Becker, “so it’s natural the subject should come up. At one time I felt that I would be morally obliged to blow my brains out at this age, but I no longer feel that.

“At this stage of the game, in 1980, if I had to be 30 or 19, I’d rather be 30. What kind of cultural heritage does a 19-year-old have? They’re lucky if they can read. They have a thing now in New York so that they don’t teach 80 percent of the people how to read English or Spanish. It’s called bilingual education. That’s what happened to my novel last night.”

“Someone asked if we felt alienated from our audience because now they’re younger than we are,” says Fagen. “I don’t know if that’s true, but we always felt alienated. It’s not that rare a sensation.”

Becker nods and grins. “We could feel alienated at William Burroughs’ birthday party, hell, you know? Be wallflowers.”

If Walter Becker and Donald Fagen would rather be 30 than 19, it doesn’t necessarily follow that they’re in the precise musical time warp of their choosing. Gaucho flies in the face of recent rock trends, eschewing the minimalism that has marked the new wave. Flirtations with jazz on Aja have sparked outright advances on Gaucho.

Henry Van Dyke said that jazz is music invented by demons for the torture of imbeciles; Fagen and Becker fit both categories. They laugh at any implication that they are educating the pop audience to jazz forms, yet they are frank about their ability to resuscitate the genre at whim.

“I don’t listen to the radio that much now,” admits Becker, “but when I do, it’s really pap. I have to think that what we do has to sound different from songs which have no chord changes, or bad chord changes, or four of the five important musical components completely neglected. Things I hear on the radio are either very stark and raw-sounding, what they call new wave, or they’re slick and offensive. Hollywood.”

“From what I’ve heard,” says Fagen, “some of these groups that were minimal a few years ago have started to slick up quite a bit. For instance, Talking Heads, who were considered a minimalist band a couple of years ago, sound like they’re doing at least as much overdubbing as we do.

“There’s a lot of primitive Eastern music that’s been very influential to composers, and to Western eras, or at least to ours, the lack of harmonic interest is crushing, it’s deadly. But they’re doing it purposely, as I understand it. They definitely don’t want to hear any chord changes.”

“If any artist abuses his audience as a means to any end, noble or ignoble,” cuts in Becker, “he better have a damn good reason for it. You can make a machine do that. It’ll even attempt personal resolution if you tell it to.”

“Actually, if I were under the influence of extremely high-grade marijuana, and I put on a Steve Reich record, it might alter my state of consciousness.”

“Yeah, but I’ve seen you under certain circumstances take a Duke Ellington record and play it backward and forward like this,” Becker swings his arm up and down, “and call it a form of musical development, too.”

“It’s about the same thing. There’s a crisis in the avant-garde which I don’t think will ever be resolved. It’s best to take the long way around it. We like to please ourselves, and to do that we have to come up with novel structures and progressions, ways of arranging, juxtaposition of lyrics and music. If you want to call that avant-garde because it’s new and original, then I guess it is. Originality itself is shocking. You don’t have to be bad to be shocking.”

“In other words,” says Becker, “if you’re gonna put tits on a bull, make ’em nice tits.”

Fagen admits that their music reclaims more traditional forms, “but only to the extent that we’re able to reach a mass audience. They’re hearing it for the first time. It’s a pleasant sideline if somebody hears our records and is induced to listen to jazz, but we have no missionary ambitions.”

“I wish it were possible the way it once was to open a door and have everything there the way it should be,” says Becker. “But there’s nothing behind the door now, the tenants have been evicted. People I know now who are discovering jazz, that’s not the best news they ever heard. Why not? Because they’re not hearing good jazz. They’re hearing a lot of garbage that’s also called jazz.

“It’s confusing. In the jazz bins, it’s half garbage and half Miles Davis. But if you buy the one bad Roland Kirk album, there you go, you’re in trouble. The one crummy record that didn’t exist 20 years ago. There are a lot of guys practicing jazz in public that should be at home practicing, or not be allowed to practice.

“I’m at the age where right when I wanted to go see a guy or could get into the clubs because of the drinking laws, he died. It was an accident of when I was born. There may be a resurrection in interest, but not musicians. Once they’re dead, they stay dead. That’s the rule. No exceptions.

“The Harvard Dictionary of Music is education. Steely Dan is entertainment. It would be nice if somebody heard our music and went home and something wonderful happened, or he says to his record company, ‘I don’t have to tour, because they don’t,’ and he doesn’t have to spend all that dead time in purgatory. If someone built an electric strappado and cited us as an influence, we’d go to our graves smiling, but I don’t believe in education.”

For all the pessimism, Becker and Fagen do have hope for the future of rock and roll. “I don’t know if rock and roll has really even begun to congeal,” says Fagen. “I think, being optimistic, it could be only a small part of something which is to come. It’s too early to judge.”

“Rock and roll may only be in the minstrel-show stage,” agrees Becker. Let’s look on the bright side. It hasn’t had a chance to get good because it’s not supposed to get good. Economics. Now, if things were allowed to happen by themselves maybe it would become organic, it would change.”

“Who knows what’s gonna come out of the Third World. A few years ago you had reggae, which is at least to my ears a rather recent innovation, it’s something new,” says Fagen. “That’s encouraging.”

“It’s been absorbed now. It’s like Latin percussion, your South American influences, conga drums on a rock and roll record. If the bass player doesn’t come down on one, it doesn’t stop any traffic. That helps to keep the thing going, it makes it possible to get new kinds of grooves going.” Becker pauses for a moment.

“If I were realistic, if I were king. . . Maybe if we’re lucky, it’ll turn into jazz again. Coming up: Jazz Age! Look at this guy’s shoes! Jazz Age! Top Band. Jazz Age! Coming up now. Trumpets. Everything.”

No comments yet.